Tag Archives: conservation

Native American tribes strive to save the lamprey

Lamprey used to be an important source of food for Native American tribes living along the northwestern coast of North America, and the fish was once upon a time harvested in ample amounts from rivers throughout the Columbia Basin, from Oregon to Canada.

First census finds fewer White Sharks than expected in northeast Pacific Ocean

A team of researchers headed by Taylor Chapple, a UC Davis doctoral student, has made the first rigorous scientific estimate of White shark (Carcharodon carcharias) numbers in the northeast Pacific Ocean.

The researchers used small boats to reach spots in the Pacific Ocean where white whales congregate and lured them into photo range with a fake seal attached to a fishing line. Out of all the photographs taken, 321 photos showed dorsal fin edges. The dorsal fin edges of white sharks are jagged and each individual displays its own unique pattern. The photographs could therefore be used to identify individual sharks – 131 in total.

The research team then entered this information into statistical models to estimate the number of sharks in the region. According to their estimate, there are 219 adult* and sub-adult** white sharks in this area.

“This low number was a real surprise,” says Chapple. “It’s lower than we expected, and also substantially smaller than populations of other large marine predators, such as killer whales and polar bears. However, this estimate only represents a single point in time; further research will tell us if this number represents a healthy, viable population, or one critically in danger of collapse, or something in-between.”

The white shark population in the northeast Pacific Ocean is one of three known white shark populations in the world; the other two are found off the coast of South Africa and off Australia/New Zealand, respectively.

Earlier studies using satellite tagging have shown that the white sharks of the northeast Pacific Ocean have an annual migration pattern. Each year, they move from the region off the coast of central California and Mexico’s Guadalupe Island to the Hawaiian Islands or to an area of open ocean located between the Baja Peninsula and Hawaii. The latter destination has even been dubbed “White Shark Café” due to its popularity among white sharks. After spending some time away from the mainland, the sharks journey back to coastal waters.

“We’ve found that these white sharks return to the same regions of the coast year after year,” says Barbara Block, marine biologist at Stanford University and one of the co-authors of the pioneering white shark census. “It is this fact that makes it possible to estimate their numbers. Our goal is to keep track of our ocean predators.”

The paper “A first estimate of white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, abundance off Central California” (http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2011.0124) has been published in the journal Biology Letters (http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org).

* Adult white sharks are the ones that have reached sexual maturity, something which happens when the male is roughly 13 feet and the female is about 15 feet in length.

**Sub-adults are roughly 8 feet or longer (but has not reached sexual maturity); at this size their dietary focus shifts from mostly fish to mostly marine mammals.

Study co-authors

- Taylor K. Chapple, Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, University of California Davis, USA and Max Planck Institute, Germanyhttp://www.topp.org/user/taylorchapple

- Salvador J. Jorgensen, Hopkins Marine Station of Stanford University, USA and Monterey Bay Aquarium, USAhttp://www.topp.org/blog/salvo

- Scot D. Anderson, Point Reyes National Seashore, USA

- Paul E. Kanive, Department of Ecology, Montana State University, USA

- A. Peter Klimley, Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, University of California Davis, USAhttp://wfcb.ucdavis.edu/people/faculty/klimley.php

- Louis W. Botsford, Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, University of California Davis, USAhttp://wfcb.ucdavis.edu/people/faculty/botsford.php

- Barbara A. Block, Hopkins Marine Station of Stanford University, USAhttp://www-marine.stanford.edu/block.htm

Funding

- The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) Fisheries through the Partnership for Education in Marine Resource and Ecosystem Management (PEMREM) and the NOAA Fisheries/Sea Grant Fellowship Program

- The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

- The National Parks Service’s Pacific Coast Science and Learning Center

- Monterey Bay Aquarium

- UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory

- Patricia King, member of the Point Reyes National Seashore Association

Florida researchers use satellites to find out more about the elusive Hammerhead shark

Using satellite tag technology, research assistant professor Neil Hammerschlag and his colleagues have tracked a hammerhead shark during 62 days, as it journeyed from the southern coast of Florida to the middle of the Atlantic off the coast of New Jersey.

The straight line point-to-point distance turned out to be 1 200 kilometers (745 miles).

“This animal made an extraordinary large movement in a short amount of time,” says Hammerschlag, director of the R.J. Dunlap Marine Conservation Program at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science. “This single observation is a starting point, it shows we need to expand our efforts to learn more about them.”

The hammerhead is believed to have been following prey fish off the continental slope, and it was probably prey that caused it to enter the Gulf Stream current and open-ocean waters of the northwestern Atlantic.

The study headed by Hammerschlag is a part of a larger effort to satellite track tropical sharks to find out if any areas are especially important for their hunting, mating and rearing of young. Hammerschlag also wish to document their migration routes.

“This study provides evidence that great hammerheads can migrate into international waters, where these sharks are vulnerable to illegal fishing,” says Hammerschlag. “By knowing the areas where they are vulnerable to exploitation we can help generate information useful for conservation and management of this species.”

More information can be found in the paper “Range extension of the Endangered great hammerhead shark Sphyrna mokarran in the Northwest Atlantic: preliminary data and significance for conservation“, published in the current issue of Endangered Species Research. The paper’s co-authors include Hammerschlag, Austin J. Gallagher and Dominique M. Lazarre of the University of Miami and Curt Slonim of Curt-A-Sea Fishing Charters.

18 baby dolphins found dead in the Gulf of Mexico

On February 21, three baby dolphins were found dead on the shores of Horn Island, and on February 22 the finding of a fourth carcass was confirmed by The Institute for Marine Mammal Studies (IMMS). This brings the amount of dead infant dolphins reported since January up to 18. Since the beginning of the year, 10 adult dolphins have also been found dead.

Located roughly 12 miles (20 km) south of Ocean Springs, Mississippi, Horn Island is one of several islands that make up the Gulf Islands National Seashore Park. National Resource Advisory employees are currently working with BP cleanup crews on the island.

Blair Mase, marine mammal stranding coordinator at The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is concerned about the high number of wash up dead dolphins.

“We’re definitely keeping a close eye on this situation,” says Mase. “We’re comparing this to previous years, trying to find out what’s going on here.”

We are now early in the birthing season for dolphins in the area, and so far, 18 bodies of baby dolphins have been found where the baby was either stillborn or died shortly after birth.

“We’re trying to determine if we do in fact have still births,” says Mase. “There are more in Mississippi than in Alabama and Louisiana. With the oil spill, it is difficult. We’re trying to determine what’s causing this. It could be infectious related. Or it could be non-infection. We run the gamut of causes.”

The necropsy of the dead dolphins will hopefully help shed some light on the situation.

Fake seagrass help us learn how to save dwindling fish populations

A large amount of New Zealand’s seagrass have been killed by sediments released from land development. The seagrass bed at Whangarei Harbour has for instance been reduced from 14 sq km in the 1960s to virtually non-existant today. And sedimentation this is not a new problem – between 1959 and 1966 Tauranga Harbour lost 90 per cent of its seagrass.

Researchers at New Zealands’s National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research are now fitting the floor of the Whangapoua Estuary with plastic seagrass in an attempt to show how New Zealand’s fish stocks could be boosted by restoring the seagrass habitats. The “seagrass” consists of plastic fronds attached to wire frames, and the length of the fronds varies from 5 cm to 30 cm.

“We made them with tantalising long blades of artificial grass, the things fish really go for,” says NIWA fisheries ecologist Dr Mark Morrison. “What we found, initially, is that fish are really looking for shelter and seagrasses provide good protection to fish.”

The largest density of fish could be found where the density of seagrass was also at its largest.

Fish is now being tagged to make it possible for the researchers to track both growth rate and survival rate.

Atlantic Tuna Commission Takes Unprecedented Action to Protect Sharks: “Particularly Pleased”

Shark Advocates International is giving a warm welcome to progress towards helping conserve sharks. This progress was made at the annual meeting of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) this week.

There were a record number – six to be exact – proposals for shark measures, the parties of the ICCAT agreed to put a stop to the retention of oceanic whitetip sharks, prohibit exploiting of hammerheads, and set up a process for punishing countries who do not get with the program and accurately report catches and reduce fishing pressure on shortfin mako sharks. The proposals to stop the retention of abundant thresher and porbeagle sharks were thrown out as a measure to help ICCAT gain a stronger position to ban shark “finning” by prohibiting removing the fins of a shark at sea.

“ICCAT has taken significant steps toward safeguarding sharks this week, but much more must be done to effectively conserve this highly vulnerable species,” explained President of Shark Advocates International, Sonja Fordham, who serves on the US ICCAT Advisory Committee and has participated in ICCAT meetings since 2004. “We are particularly pleased with the agreements aimed at protecting oceanic whitetip sharks and reducing international trade in the fins of hammerhead sharks, as well as US efforts to conserve mako sharks.”

It’s good to see that progress is being made, and all parties involved are rather pleased that the meetings have gone so well so far. Hopefully, this means a better world for sharks.

80 Year Old Shark Gets Groove On

After a stint of nineteen years in the park, the only sawfish at Six Flags Discovery Kingdom, which is thought to be somewhere in the vicinity of eighty years of age, has been sent off to a breeding program in New Orleans, officials have commented.

Michael Mraco, the park Animal Care Director, has commented that this particular species of shark can live for two centuries “so he’s not the old man we thought he was”.

“Buzz” has been living among five or six shark species at the Shark Experience in the park until this past Friday when he headed for his new home.

“We all feel this is good for Buzz and good for the species, which is endangered,” commented John Schultz, Curator of Fish for the park.

Muraco has explained how this transfer came to take place, and just how an eight decade old shark makes its way to a breeding program.

“This led to a conversation with the Autobahn Aquarium in New Orleans, and they mentioned there are only a handful of these animals left in United States and that they’re at risk in the wild and they asked how we’d feel about a cooperative breeding program,” Muraco explained.

And there you have it.. That is how an eighty year old shark is getting the chance to get his groove back on, and help save his species from extinction. It’s a tough job, but “Buzz” certainly seems up to the task.

Experts Backing Law Which Bans Shark Fishing

Conservationists and researchers are lashing out after the 11th fish was killed in BDA waters in the past week.

Are sharks dangerous man eating monsters, an excellent source for protein, or just another example of humanity being cruel and exploiting the oceans?

An 11 foot tiger shark being hacked to bits on a dock in Somerset this week really got the juices flowing in a lot of people.

The children seemed to be at ease, eagerly awaiting their turn to have their photo taken with the beast, however some other concerned citizens have said that the endangered animal had simply been killed for the sport of it.

The owner of the SCUBA firm Blue Water Diving, Michael Burke, has said that he believes that Bermuda should follow Palua and the Maldives example, and protect sharks through legislation.

He explained: “I really don’t see the need to catch a tiger shark. There’s very little use for them. It is not a good eating fish.

“We don’t need to do that anymore. It is a different world we live in.

“Those images of hunters standing with their feet on a lion’s head as some sort of trophy, it is an anachronism.

“Palau has banned shark fishing, we could do the same. We did it for turtles in the 1800s, why not sharks?”

Experts, and the local community seem to be in agreement with him, and will soon have a vote to see about banning the killing of these endangered sharks.

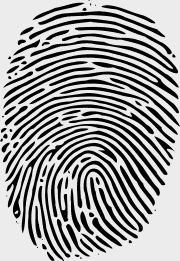

85 Different species of Shark Have Been Genetically Fingerprinted

The DNA mapping of these sharks is thought to be rather significant in terms of being able to identify the most threatened species. Now it will be easier to help manage programs to save them. The program is being headed by the Ministry of Earth Sciences, and is part of an ongoing survey and assessment plan for mapping deep sea species in the Indian Ocean.

India is currentlt the second largest shark fishing nation, many species of shark are killed for their fins, oil and their meat.

The actual genetic fingerprinting of the sharks was done by a team of scientists from the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute in conjunction with the Kochi regional center of the National Bureau of Fish Genetic Resources in Lucknow.

The shark samples were collected in the Gujurat, Tuticorin, Conchin fisheries harbour and also the Neendakara fishing harbour. The researchers were performing the fingerprinting under the direction of the N.G.K. Pillai, of the Pelagic Fisheries Division of the Institute, along with the help of A. Gopalakrishnan of the bureau. Other members on the team included K.K. Bineesh, K.V. Akhilesh and K.A. Sajeela.

This genetic fingerprinting will greatly aid in the identification of the different shark species from tissue samples. Most shark species are found at a depth of around 250 meters and little is actually known about them. This project is aiming to change that, and bring the sharks into the public eye.

Indonesian Navy sends warships to protect fish

“The five warships and reconnaissance plane have conducted routine patrols in the Natuna waters as part of efforts to reduce the number of fish thefts,” S.M. Darojatim, Commander of the Main Naval Base IV Commodore, announced Tuesday.

He also stated that the Natuna waters and the South China Sea were vulnerable to a number of criminal offences, including fish and coral thefts.

“The Pontianak naval base has so far secured the West Kalimantan waters well so that it sets a good example to other naval bases to safeguard the Indonesian waters,” said the commander.

Natuna Sea Facts

The Natuna Sea is a part of the South China Sea and home to an archipelago of 272 islands, located between east and west Malaysia and the Kalimantan (the Indonesian portion of the island Borneo). The islands form a part of the Indonesian Riau province and is the northernmost non-disputed island group in Indonesia.

The islands are populated with roughly 100,000 people, most of them farmers and fishermen. The beaches are important nesting sites for sea turtles and the surrounding waters are filled with biodiverse coral reefs. The archipelago is also famous for its rich avifauna with over 70 different described species of bird, including rare ones like the Natuna Serpent-eagle and the Lesser Fish-eagle. The islands are also home to primates, such as the Natuna Banded Leaf Monkey which is considered one of the 25 most endangered primates in the world.