Tag Archives: wrecks

Medieval shipwrecks threatened by the spread of shipworm into the Baltic Sea

Not really a worm

Shipworms are not actually worms but saltwater clams with much reduced shells. They are notorious for borrowing into and gradually destroying wooden structures in saltwater; earning the nickname “termites of the sea”.

There are 65 different know species of shipworm but Teredo navalis is the only one currently known to spread into the Baltic Sea via the Great Belt. Teredo navalis forms up to 30 cm deep tunnels in submerged wood and is difficult to detect since it remains hidden inside the tunnel. It has a life expectancy of 3-4 years.

Teredo navalis can survive in a salinity of 4-6 practical salinity unit (PSU) for short periods of time but can not reproduce unless the salinity is at least 8 PSU. The salinity of the Baltic Sea decrease the further north you get with the Stockholm Archipelago sporting an average salinity of roughly 5 PSU.

The shipworm is capable of completely destroying large maritime archaeological finds in only 10 years, and while it has avoided the Baltic Sea in the past, since it does not do well in low salinity water, it can now be spotted along both the Danish and German Baltic Sea coasts.

14th century shipwrecks under attack

“Wrecks that have been resting unharmed since the 14th century have now been attacked off the coast of Rügen in Germany, and we are also noticing attacks along the Swedish coast, including destruction of the Ribersborg cold bath house in Malmö,” says Christin Appelqvist, doctoral student at the Department of Marine Ecology, University of Gothenburg.

Appelqvist and her colleagues suspect that increased water temperatures may be helping the shipworm to tolerate a lower salinity.

One of the objectives of project WreckProtect is to develop methods for the preservation and protection of shipwrecks. It might for instance be possible to cover the wrecks with geotextile and bottom sediment.

100,000 wrecks may be at risk

Thanks to the absence of Teredo navalis there is currently around 100,000 well preserved shipwrecks resting in the Baltic Sea, a true treasure for historians and archaeologists. If the shipworm continues to spread these ships may vanish before anyone has a chance to explore them.

“Around 100 wrecks are already infested in the Southern Baltic, but yet it hasn’t even spread past Falsterbo. We know it can survive the salinity of the Stockholm archipelago, although it needs water with higher salinity than that to be able to reproduce,” says Appelqvist.

* Christin Appelqvist, Department of Marine Ecology, University of Gothenburg

http://www.marecol.gu.se/Personal/Christin_Appelqvist/

* Jon Havenhand, Department of Marine Ecology, University of Gothenburg

http://www.tmbl.gu.se/staff/JonHavenhand.html

Picture credit: http://www.science.gu.se

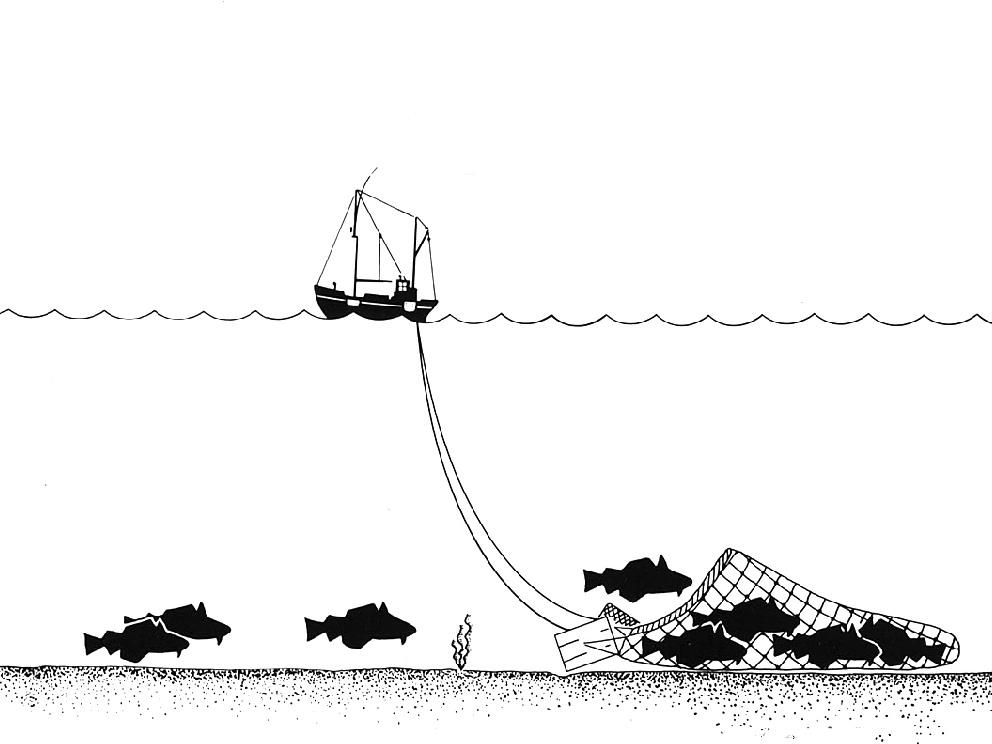

Are trawlers obliterating historic wrecks?

An example of the damage trawlers can cause is the wreck of HMS Victory, a British warship sunk in the English Channel in 1744. Trawling nets and cables have become entangled around cannon and ballast blocks, and three of the ship’s bronze cannons have been displaced. One of them, a 42-pound (19 kg) cannon weighing 4 tonnes, has been dragged 55 metres (180 feet) and flipped upside down. Two other cannon recovered by Odyssey Marine Exploration last year show fresh scratches from trawls and damage caused by friction from nets or cables.

“We know trawlers work the Victory site because one almost ran us down while we were there,” says Tom Dettweiler, senior project manager of Odyssey Marine Exploration.

“It turns out that Victory is right in the middle of the heaviest trawling area in the Western Channel,” says Greg Stemm, chief executive of the company. “We were shocked and surprised by the degree of damage we found in the Channel, he continues. “When we got into this business, like everyone else we thought that beyond 50 or 60 metres, below the reach of divers, we’d find pristine shipwrecks. We thought we’d be finding rainforest, but instead found an industrial site criss-crossed by bulldozers and trucks.”

While surveying 4,725 sq miles (12,300 sq km) of the western Channel, Odyssey Marine Exploration found 267 wrecks, of which 112 showed evidence of being damaged by bottom trawlers. That is over 40 percent.

The English Channel has been a busy area for at least three and half millennia and was thought to be littered with wrecks. In these fairly cold waters, wooden ships tend to stay intact for much longer periods of time than they would in warm tropical regions. Strangely enough, Odyssey Marine Exploration found no more than three pre-1800 wrecks when surveying the area using modern technology sensitive enough to disclose a single amphora. According to historic estimations, at least 1,500 ships have been lost in these waters so finding no more than three pre-1800 wrecks calls for further investigation.

Odyssey Marine Exploration blames bottom trawlers for the lack of wrecks. “The conclusion and fear is that the vast majority of pre-1800 sites have already been completely obliterated by the deep-sea fishing industry,” says Sean Kingsley, of Wreck Watch International, the author of the Odyssey report.

Odyssey Marine Exploration is the world’s only publicly-listed shipwreck exploration company and critics argue that these American treasure hunters are overstating the damage for their own gain.

“You have to ask why Odyssey is doing such a study,” said Robert Yorke, chairman of the Joint Nautical Archaeology Policy Committee. “They want to pressurise the UK Government to allow them to get at the wreck . . . the Victory hasn’t disappeared since 1744; it’s not going to disappear tomorrow.”

The Ministry of Defence has jurisdiction over warships’ remains and it has asked English Heritage for an assessment of the threats to the site. English Heritage has a policy of leaving shipwrecks untouched on the seabed unless a definite risk can be shown.

Yo ho ho and a bottle of rum

A company named Ghost Pros is currently exploring the ship wrecks of Florida in search not of gold, silver or precious stones but of ghosts. The company is using the latest underwater ghost-detection technology, including submersible high powered sonar listening devices. Ghost Pro divers have also teamed up with Tampa’s Sea Viewers, the makers of high definition studio cameras which will be used to develop under water rovers.

“We’re listening to everything and anything we can down there,” says Ghost Pros’ Lee Ehrlich, explaining that you have to know what is not a ghost before you can find one. “[…] before you can tell you need to know what that ship sounds like alone,” he says.

Unlike Ghost Busters, Ghost Pros doesn’t get paid to hunt ghosts, but the search does generate a lot of attention from ghost aficionados and ghost critics, as well as from the general media. Hunting for the para-normal has proven to be an excellent way of creating some very normal buzz for Ehrlich and his companions, who – when not hunting down the ghosts of voyages past – are developing advanced submersibles for search and rescue operations.

As a diver, I would like to recommend any readers of this blog to leave the deep sea ghost hunting to professionals like Ehrlich and his crew. If you start seeing ghosts while scuba diving, make a safe ascendance and wait for the nitrogen poisoning to wear off.