Tag Archives: thrawling

Why are whales in Korean and Japanese waters more accident prone than others, scientists wonder

Most IWC* member countries accidently kill whales, e.g. by unintentionally ramming into them with motorized vessels or by using fishing methods that may entangle and suffocate these air-breathing mammals as accidental by-catch. While this type of accidental deaths is reported from most member nations, Japan and South Korea have an inordinate amount of accidental by-catchs, says Professor Scott Baker, associate director of the Marine Mammal Institute at Oregon State University.

By analysing the DNA of whale-meat products sold in Japanese markets, Baker, a cetacean expert, and Dr Vimoksalehi Lukoscheck of the University of California-Irvine, found that meat from as many as 150 whales came from the coastal population. Japan’s scientific whaling program only targets whales from open ocean populations, but whales accidently killed outside the program are allowed to be sold.

Humpback Whale

Japan and South Korea are the only countries that allow the commercial sale of products derived from whales killed as accidental by-catch and the sheer number of whales represented by whale-meat products on the market suggests that there might be something fishy about these allegedly accidental kills.

They DNA study showed that nearly 46 percent of examined Minke whale products came from a coastal whale population, which has distinct genetic characteristics, and is protected by international agreements. In addition to minke whales, Baker and Lukoscheck also found DNA from Humpback whales, Bryde’s whales, Fin whales, and Western gray whales.

“The sale of bycatch alone supports a lucrative trade in whale meat at markets in some Korean coastal cities, where the wholesale price of an adult minke whale can reach as high as $100,000,” Baker said. “Given these financial incentives, you have to wonder how many of these whales are, in fact, killed intentionally.”

In January 2008, Korean police launched an investigation into organized illegal whaling in the port town of Ulsan, reportedly seizing 50 tons of minke whale meat.

Japan has asked the IWC, who is holding its annual meeting this week, to allow a small coastal whaling program in Japanese waters. This request is something that professor Baker says should be scrutinized carefully because of the uncertainty of the actual catch and the need to determine appropriate population counts to sustain the distinct stocks.

Baker and Lukoscheck have presented their findings to the IWC commission and the study will also be published in a forthcoming issue of the journal Animal Conservation.

* International Whaling Commission

History of Trawling; not a modern problem

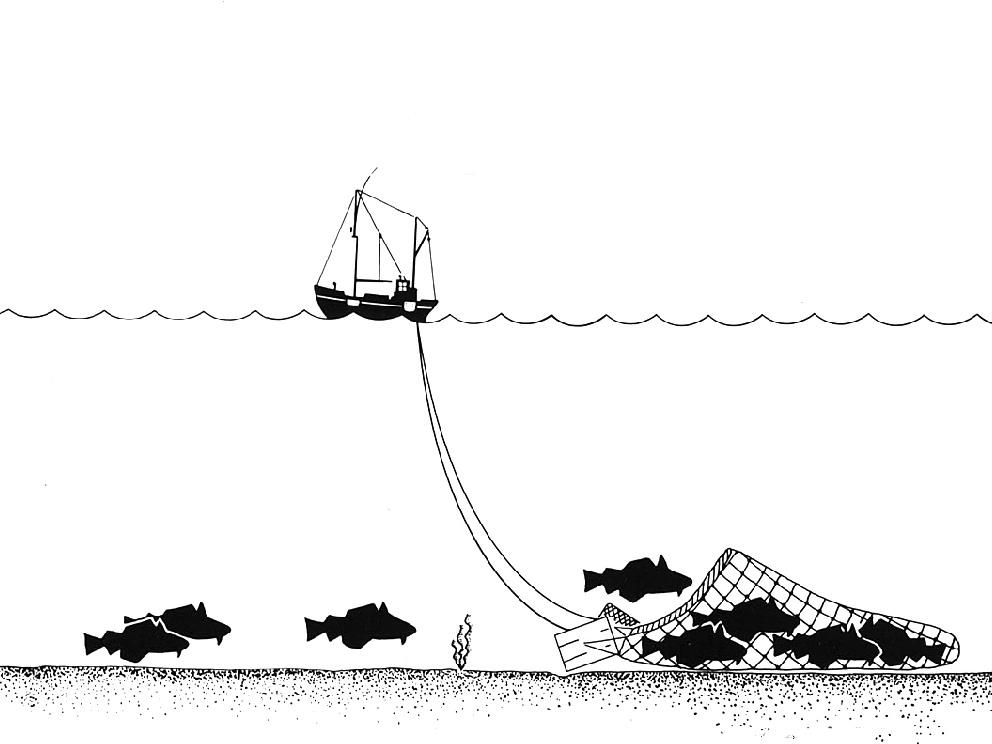

One of the earliest known complaints regarding trawling is in fact 400 years older than the U.S. Declaration of Independence and over two centuries older than all the Shakespeare plays; it dates back to the European Middle Ages but raises the same questions as we discuss to today: the effect of trawling on the ecosystem, the consequences of a small mesh size, and industrial fishing for animal feed.

During the reign of Edward III, a petition was presented to the British Parliament in 1376 calling for the prohibition of a “subtlety contrived instrument called the wondyrchoum”. According to the petition, the wondyrchoum was a type of beam trawl, which caused extensive damage to the environment in which it was used.

“Where in creeks and havens of the sea there used to be

plenteous fishing, to the profit of the Kingdom, certain fishermen

for several years past have subtily contrived an instrument

called ‘wondyrechaun’ […] the great and long iron of the

wondyrechaun runs so heavily and hardly over the ground when

fishing that it destroys the flowers of the land below water there,

and also the spat of oysters, mussels and other fish up on which

the great fish are accustomed to be fed and nourished. By which

instrument in many places, the fishermen take such quantity of

small fish that they do not know what to do with them; and that

they feed and fat their pigs with them, to the great damage of the

common of the realm and the destruction of the fisheries, and

they prey for a remedy.”

According to the letter, a wondyrchoum had a 6 m (18 ft) long and 3 m (10 ft) wide net

“[…] of so small a mesh, no manner of fish, however small, entering within it can pass out and is compelled to remain therein and be taken […].”

Another source* describes the wondyrchoun as ” […] three fathom long and ten mens’ feet wide, and that it had a beam ten feet long, at the end of which were two frames formed like a colerake, that a leaded rope weighted with a great many stones was fixed on the lower part of the net between the two frames, and that another rope was fixed with nails on the upper part of the beam, so that the fish entering the space between the beam and the lower net were caught. The net had maskes of the length and breadth of two men’s thumbs.”

The Crown responded to the 14th century complaint by letting “[…] Commission be made by qualified persons to inquire and certify on the truth of this allegation, and thereon let right be done in the Court of Chancery”.

Eventually, bans were introduced regulating the use of wondyrchoums in the kingdom and in 1583 two fishermen were actually executed for using metal chains on their beam trawls.

British fishermen continued to use trawl nets despite the ban, but trawling didn’t become the ravishingly successful fishing method of today until the advent of steam power and diesel engines in the 19th and 20th century.

In 1863, a Royal Commission was established in Great Britain to investigate the accusations against trawling, among other complaints. One of the arguments presented by the defence was a witness who, when asked what food fish eat, replied:

“There is when the ground is stirred up by the trawl. We think the

trawl acts in the same way as a plough on the land. It is just like

the farmers tilling their ground. The more we turn it over the

great supply of food there is, and the greater quantity of fish we

catch.”**

The Royal Commission also noted that when a trawler harvests an area already harvested by another trawler, the second trawler usually catches even more fish than the first. This was interpreted as a sign of the benevolence of trawlers, when in fact the high second yield is caused by how the destruction inflicted on the area by the first trawler results in an abundance of dead and dying organisms which, temporarily, attracts scavenging fish.

The result of the Royal Commission’s investigations was the abandonment of over 50 Acts of Parliament and a switch to virtually unrestricted sea fishing. Today, the 14th century issue of destructive fishing practises is more acute than ever.

* Davis, F (1958), An account of the fishing gear of England and Wales, 4th Edition, HMSO

** Roberts, C (2007), The Unnatural History of the Sea, Gaia