Tag Archives: overfishing

History of Trawling; not a modern problem

One of the earliest known complaints regarding trawling is in fact 400 years older than the U.S. Declaration of Independence and over two centuries older than all the Shakespeare plays; it dates back to the European Middle Ages but raises the same questions as we discuss to today: the effect of trawling on the ecosystem, the consequences of a small mesh size, and industrial fishing for animal feed.

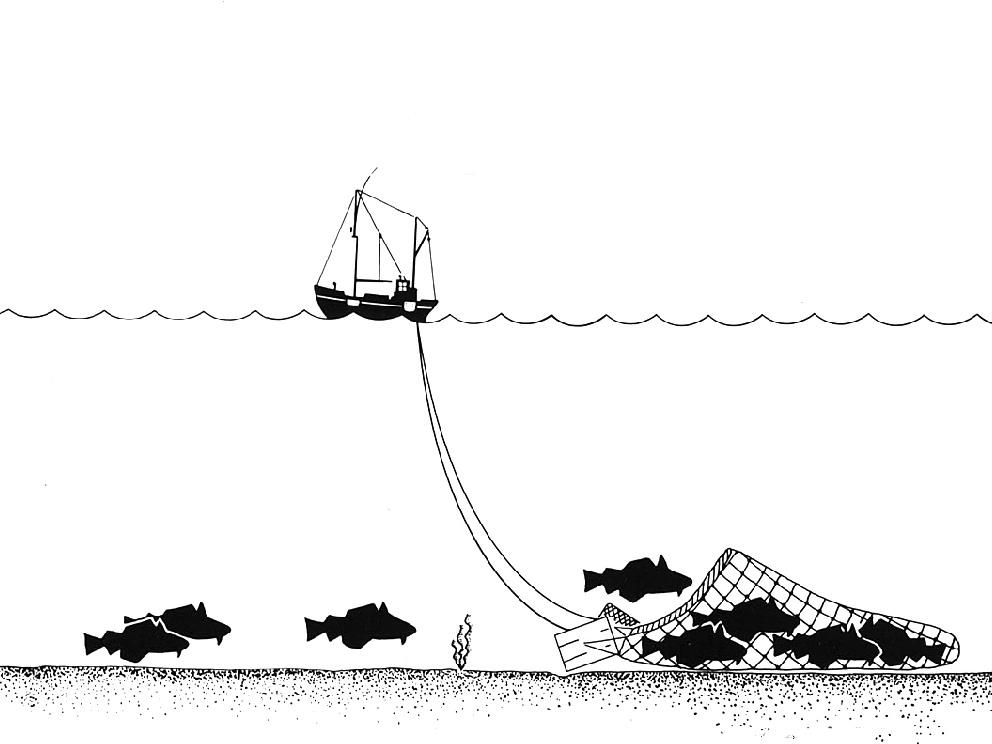

During the reign of Edward III, a petition was presented to the British Parliament in 1376 calling for the prohibition of a “subtlety contrived instrument called the wondyrchoum”. According to the petition, the wondyrchoum was a type of beam trawl, which caused extensive damage to the environment in which it was used.

“Where in creeks and havens of the sea there used to be

plenteous fishing, to the profit of the Kingdom, certain fishermen

for several years past have subtily contrived an instrument

called ‘wondyrechaun’ […] the great and long iron of the

wondyrechaun runs so heavily and hardly over the ground when

fishing that it destroys the flowers of the land below water there,

and also the spat of oysters, mussels and other fish up on which

the great fish are accustomed to be fed and nourished. By which

instrument in many places, the fishermen take such quantity of

small fish that they do not know what to do with them; and that

they feed and fat their pigs with them, to the great damage of the

common of the realm and the destruction of the fisheries, and

they prey for a remedy.”

According to the letter, a wondyrchoum had a 6 m (18 ft) long and 3 m (10 ft) wide net

“[…] of so small a mesh, no manner of fish, however small, entering within it can pass out and is compelled to remain therein and be taken […].”

Another source* describes the wondyrchoun as ” […] three fathom long and ten mens’ feet wide, and that it had a beam ten feet long, at the end of which were two frames formed like a colerake, that a leaded rope weighted with a great many stones was fixed on the lower part of the net between the two frames, and that another rope was fixed with nails on the upper part of the beam, so that the fish entering the space between the beam and the lower net were caught. The net had maskes of the length and breadth of two men’s thumbs.”

The Crown responded to the 14th century complaint by letting “[…] Commission be made by qualified persons to inquire and certify on the truth of this allegation, and thereon let right be done in the Court of Chancery”.

Eventually, bans were introduced regulating the use of wondyrchoums in the kingdom and in 1583 two fishermen were actually executed for using metal chains on their beam trawls.

British fishermen continued to use trawl nets despite the ban, but trawling didn’t become the ravishingly successful fishing method of today until the advent of steam power and diesel engines in the 19th and 20th century.

In 1863, a Royal Commission was established in Great Britain to investigate the accusations against trawling, among other complaints. One of the arguments presented by the defence was a witness who, when asked what food fish eat, replied:

“There is when the ground is stirred up by the trawl. We think the

trawl acts in the same way as a plough on the land. It is just like

the farmers tilling their ground. The more we turn it over the

great supply of food there is, and the greater quantity of fish we

catch.”**

The Royal Commission also noted that when a trawler harvests an area already harvested by another trawler, the second trawler usually catches even more fish than the first. This was interpreted as a sign of the benevolence of trawlers, when in fact the high second yield is caused by how the destruction inflicted on the area by the first trawler results in an abundance of dead and dying organisms which, temporarily, attracts scavenging fish.

The result of the Royal Commission’s investigations was the abandonment of over 50 Acts of Parliament and a switch to virtually unrestricted sea fishing. Today, the 14th century issue of destructive fishing practises is more acute than ever.

* Davis, F (1958), An account of the fishing gear of England and Wales, 4th Edition, HMSO

** Roberts, C (2007), The Unnatural History of the Sea, Gaia

Turkish government sawing of the branch their own fishermen are sitting on

The Turkish government has set their own very high catch limit for endangered Mediterranean bluefin tuna without showing any regard for internationally agreed quotas and the survival of this already severally overfished species. By telling the Turkish fishermen to conduct this type of overfishing, the Turkish government is effectively killing the future of this important domestic industry.

Turkey currently operates the largest Mediterranean fleet fishing for bluefin tuna, a commercially important species that – if properly managed – could continue to create jobs and support fishermen in the region for years and years to come. Mediterranean societies have a long tradition of fishing and eating bluefin tuna and this species was for instance an appreciated food fish in ancient Rome. Today, rampant overfishing is threatening to make the Mediterranean bluefin tuna a thing of the past.

Management of bluefin tuna is entrusted to the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), an intergovernmental organisation. Last year, the Turkish government objected to the Bluefin tuna quota that was agreed upon at the ICCAT meeting in November and is now ignoring it completely.

The agreed tuna quota is accompanied by a minimum legal landing size set at 30 kg to make it possible for the fish to go through at least one reproductive cycle before it is removed from the sea, but this important limit is being widely neglected as well. Catches below the 30 kg mark have recently been reported by both Turkish and Italian media.

To make things even worse, Mediterranean fishermen are also involved in substantial illegal catching and selling of Mediterranean bluefin tuna. This year’s tuna fishing season has just begun and Turkish fishermen have already got caught red-handed while landing over five tonnes of juvenile bluefin tuna in Karaburun.

According to scientific estimations, Mediterranean blue fin tuna fishing must be kept at 15,000 tonnes a year and the spawning grounds must be protected during May and June if this species shall have any chance of avoiding extinction in the Mediterranean. This contrasts sharply against the actual hauls of 61,100 tonnes in 2007, a number which is over four times the recommended level and twice the internationally agreed quota. The crucial spawning grounds are also being ravished by industrial fishing fleets.

By blatantly ignoring international quota limits, the Turkish government is in fact threatening not only the tuna but also the future livelihood of numerous Mediterranean fishermen, including the Turkish ones.

100 pyramids sunk off Alabama to promote marine life

Alabama fishermen and scuba divers will receive a welcome present from the state of Alabama in a few years: the coordinates to a series of man-made coral reefs teaming with fish and other reef creatures.

In order to promote coral growth, the state has placed 100 federally funded concrete pyramids at depths ranging from 150 to 250 feet (45 to 75 metres). Each pyramid is 9 feet (3 metres) tall and weighs about 7,500 lbs (3,400 kg).

The pyramids have now been resting off the coast of Alabama for three years and will continue to be studied by scientists and regulators for a few years more before their exact location is made public.

In order to find out differences when it comes to fish-attracting power, some pyramids have been placed alone while others stand in groups of up to six pyramids. Some reefs have also been fitted with so called FADs – Fish Attracting Devices. These FADs are essentially chains rising up from the reef to buoys suspended underwater. Scientists hope to determine if the use of FADs has any effect on the number of snapper and grouper; both highly priced food fishes that are becoming increasingly rare along the Atlantic coast of the Americas.

Early settlers and late followers

Some species of fish arrived to check out the pyramids in no time, such as grunt and spadefish. Other species, like sculpins and blennies, didn’t like the habitat until corals and barnacles began to spread over the concrete.

“The red snapper and the red porgies are the two initial species that you see,” says Bob Shipp, head of marine sciences at the University of South Alabama. After that, you see vermilion snapper and triggerfish as the next order of abundance. Groupers are the last fish to set in.”

Both the University of South Alabama and the Alabama state Marine Resources division are using tiny unmanned submarines fitted with underwater video cameras to keep an eye on the reefs and their videos show dense congregations of spadefish, porgies, snapper, soap fish, queen angelfish and grouper.

“My gut feeling is that fish populations on the reefs are a reflection of relative local abundance in the adjacent habitat,” says Shipp. “Red snapper and red porgy are the most abundant fish in that depth. They forage away from their home reefs and find new areas. That’s why they are first and the most abundant.”

What if anyone finds out?

So, how can you keep one hundred 7,500 pound concrete structures a secret for years and years in the extremely busy Mexican Gulf? Shipp says he believes at least one of the reefs has been discovered, since they got only a few fish when they sampled that reef using rod and reel. Compared to other nearby pyramid reefs, that yield was miniscule which may indicate that fishermen are on to the secret. As Shipp and his crew approached the reef, a commercial fishing boat could be seen motoring away from the spot.

Madagascar!

Madagascar, a large island situated in the Indian Ocean off the south-eastern coast of the African continent, is home to an astonishing array of flora and fauna. Madagascar, then part of the supercontinent Gondwana, split from Africa about 160 million years ago and became an island through the split from the Indian subcontinent 80-100 million years ago.

Madagascar is now the 4th largest island in the world and its long isolation from neighbouring continents has resulted in an astonishingly high degree of endemic species; species that can be found nowhere else on the planet. Madagascar is home to about 5% of the world’s plant and animal species, of which more than 80% are endemic to island. You can for instance encounter Appert’s Tetraka bird (Xanthomixis apperti), the carnivorious Fossa (Cryptoprocta ferox) and over 30 different species of lemur on Madagascar. Of the 10,000 plants native to Madagascar, 90% are endemic.

The diverse flora and fauna of Madagascar is not limited to land and air; you can find an amazing array of creatures in the water as well – including a rich profusion of endemic fish species. Unfortunately, the environment on Madagascar is changing rapidly and the fish – just like most of the other creatures – risk becoming extinct in the near future.

The fishes of Madagascar currently have to deal with four major threats:

- Deforestation

- Habitat Loss

- Overfishing

- Invasive species

In a response to this, and to educe people around the world about the fish of Madagascar, aquarist Aleksei Saunders have created the website Madagascar’s Endangered Fishes on which he shares his knowledge of Madagascan fish species and the perils they’re facing, but also highlights all the things we can do to improve the situation.

The site focuses on freshwater fish conservation and captive breeding, since collection of wild fish to bring endangered species into captivity for managed reproductive efforts plays a large part of the conservation effort in Madagascar.

In addition to the website, Alex is also gives power-point presentations on husbandry and conservation breeding of Madagascar’s endemic fish fauna, since more and more aquarists around the world are taking a large interest in doing their part to help endangered fish species.

Alex has worked with fish since 1990 and it was through his work as an aquarist at Denver Zoo he became enthralled with the ichthyofauna of Madagascar. During the early 1990s Denver Zoo started a conservation program with the endemic freshwater fishes of Madagascar and in 1998 Alex got the chance to pay his first, but certainly not last, visit to the island. Today, his trips primarily focus on educating the Malagasy on their wonderful natural heritage and ways of conserving it, assessing the condition of native freshwater habitats and the fish population therein, and collecting wild fish for managed captive breeding. Alex now manages on of the most diverse collections of Madagascan endemic fishes in North America, including 5 species of rainbowfish, 4 species of cichlid, and 3 killifish species.

With this site I hope to educate, motivate, and stimulate people into action to help save Madagascar’s endangered fishes. Please look around the site. There are sections for fish hobbyists, adventure travellers, conservation biologists, and just those curious about the world in which we live.

Cheers,

Aleksei Saunders

Can Catch Shares Prevent Fisheries Collapse?

This week, Science published the study “Can Catch Shares Prevent Fisheries Collapse?” by Costello[1], Gaine[2] and Lynham[3], which may be used as a road map for federal and regional fisheries managers interested in reversing years of declining fish stocks.

The study has already received a lot of praise from environmental groups, including the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) who says that the study shows how the overfishing problem can be fixed by implementing catch shares. “We can turn a dire situation into an enormous opportunity to promote better food security, create jobs and revive ecosystems,” says David Festa, vice president and director of the oceans program at EDF.

Catch share programs is intended to replace complex fishing rules and hold fishermen directly accountable for meeting scientifically determined catch limits. In a catch share program, fishermen are granted a percentage share of the total allowable catch, individually or in cooperatives. They can also be given exclusive access to particular fishing zones, so called territorial use rights. As long as the fishermen do not harvest more than their assigned share, they will retain a comparatively high flexibility and decide for themselves when to carry out the fishing, e.g. depending on market fluctuations and weather conditions.

“The trend around the world has been to fish the oceans until the fish are gone,” says Festa. “The scientific data presented today shows we can turn this pattern on its head. Anyone who cares about saving fisheries and fishing jobs will find this study highly motivating.”

As the fishery improves, each fisherman will find that the value of his or her share grows. This means that fishermen will be financially motivated to meet conservational goals.

In January 2007, a catch share system for red snapper went into effect in the Gulf of Mexico, causing the 2007 commercial snapper season to be open 12 months a year for the first time since 1990. According to EDF, fishermen in the area now earn 25% more and wasteful bycatch has dropped by at least 70%.

[1] Christopher Costello, Associate Professor of Environmental and Resource Economics at the Donald Bren School of Environmental Science & Management, University of California

[2] Steve Gaine, Professor of Ecology, Evolution & Marine Biology, University of California

[3] John Lynham, Assistant Professor in the Economics Department at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa