Tag Archives: oil spill

Nungesser Implores Coast Guard to Mop Up Mess Leftover From BP Spill

With the black goo from the BP oil spill making its way to the once clean shores, Billy Nungesser, the President of Plaquemines, has pleaded with the U.S. Coast Guard to help finish mopping up the mess BP left behind, before beginning to restore the area.

“The Coast Guard’s role through this whole thing has been to get in the way of local government,” Nungesser said Wednesday. “We’re still fighting. They want to downsize.”

Nungesser has commented that thousands of gallons of the black BP goo is making its way into the Parish’s delicate marshes and swampland.

Paul Zakunft, the Rear Admiral of the Coast Guard as well as the federal governments on scene coordinator, commented on Wednesday that there is a lot of the BP goo left to mop up, and the Coast Guard won’t be backing down from the challenge of doing so.

Even though the BP fiasco supposedly ended when they capped the well over 2 and a half months ago, over 20,000 workers ae still mopping up the mess from 588 miles of shoreline as well as the marshlands of Louisiana, Zakunft explained.

Two of the areas which are in desperate need of a cleanup are Barataria Bay and Bay Jimmy, he added.

The blame has been laid on the bad weather and high tides in the month of June, for spreading the black goo to where it isn’t welcome.. Well, it’s time someone stopped making excuses, and started mopping!

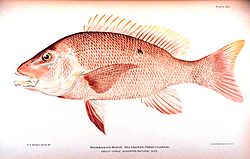

Despite Oil Spill, Fish Fry Showing up In Record Numbers in Gulf of Mexico

Snapper fry are all over the place. There are also trout, grunt and grouper fry all over the place as well. The early tabulation of the annual count in the beds of grass spattered about the northern part of the Gulf of Mexico seems to suggest that the larvae of some kinds of fish have survived the BP oil fiasco, and what’s more, there are swarms of them.

“My preliminary assessment, it looks good, it looks like we dodged a bullet. In terms of the numbers of baby snapper and other species present in the grass beds, things look right,” commented a scientist with the University of North Carolina’s Institute of Marine Science, Joel Fodrie, who has been actively involved in the study of seagrass meadows along the coast for the past five years.

Joel’s group has taken samples of the different sea life in the grass beds in Alabama, Mississippi, and the Florida Panhandle. They will be taking a sample from around Louisiana’s Chandeleur Islands come this Autumn.

Back at the height of the fiasco, when a seemingly endless stream of oil was floating about on the surface, researchers were most concerned as to whether the trillions of larvae which hatch each spring offshore would survive the severe contamination of the spill.

It’s looking like they did, and it’s a good thing too. It just goes to show you that mother nature is more resilient than we give her credit for. There is hope yet for the Gulf to make a full recovery, and that folks, is good news indeed.

Oil Spill in Gulf Effecting Seahorses, Not Over Yet:

There are tens of thousands of dwarf seahorses trying to survive in the oil infested Gulf of Mexico, and a researcher from the University of British Columbia is saying that their difficulties serves as a warning to not let BP to expand its operations to the West Coast.

Now the dwarf seahorse is at great risk of becoming extinct after the BP mess happened this past April, and it isn’t being helped any by the non-friendly methods for clearing up the mess, commented the director of the international project Seahorse conservation group, Amanda Vincent.

“We’re concerned that some lessons be learned for Canada from this fiasco,” Vincent commented during a press conference this past Tuesday.

“If we were to have an oil spill on this coast, either from tanker traffic or from drilling — if the moratorium were lifted — then we would also see them and everything else in their habitats severely affected.”

While a provincial, as well as federal, moratorium is in place against any kind of oil exploration on the north coast of British Columbia is in effect, the First Nations and other environmental organizations have cautioned of the dangers of putting in an oil pipeline.

And with what happened in the Gulf of Mexico who could blame them? We really need to step back, and force the big oil companies to take extra precautionary measures, before allowing to operate anywhere else in the world…

Scientists Hot on the Trail of Huge, Underwater Oil Plume In Gulf Of Mexico

Researchers backed by the NSF (National Science Foundation) and in conjunction with the WHOI (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) have discovered a plume of hydrocarbons which is more than 3,000 feet below the surface of the Gulf of Mexico and is thought to be 22 miles long at minimum. This plume is the residue of the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill.

The 650 foot high, and 1.2 mile wide, plume of trapped hydrocarbons was discovered in the midst of a ten day subsurface sampling effort which took place from the 19th of June, until the 28th of June this year near the wellhead. The results have given a clear indication of where the oil has gone as the slicks on the surface have been shrinking and disappearing.

“These results create a clearer picture of where the oil is in the Gulf,” commented Christopher Reddy, a WHOI marine geochemist and one of the authors of a paper on the results that appears in this week’s issue of the journal Science.

This investigation – which was made possible by three quick action grants from the chemical and oceanography program at the NSF, with additional money made available by the US Coast Guard and NOAA via the Resource Damage Assessment Program – has confirmed that a large flowing plume was discovered which had

“petroleum hydrocarbon levels that are noteworthy and detectable,” Reddy explained.

So it seems we have not yet seen the end of the dreadful BP Oil Spill. While there has been no talk about what to do about this potentially disastrous situation, they are hard at work on it, but it could be months before an answer is found.

80% Of Oil From the Gulf Of Mexico Spill Is Still Lurking About: “The Oil Is Still Out There”

The report was written by five accomplished marine researchers, and strongly goes against the reports issued by the media, which state that only 25% of the oil from the BP spill is still out there.

“One major misconception is that oil that has dissolved into water is gone and, therefore, harmless,” director of Georgia Sea Grant and professor of marine sciences in the University of Georgia Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, Charles Hopkinson explains. “The oil is still out there, and it will likely take years to completely degrade. We are still far from a complete understanding of what its impacts are.”

The report was written in conjunction with Jay Brandes, the associate professor of the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography; Samantha Joye, a professor of marine sciences at the UGA; Richard Lee, professor emeritus at Skidaway; and Ming-yi Sun, a professor of marine sciences at the UGA.

This group of researchers have take a look at the data taken from the Aug 2nd National Incident Command Report, which estimated an “oil budget” which was widely interpreted as suggesting hat only 25% of the oil from the catastrophic spill remained in the waters.

Oiled Marshes Showing Signs of Recovery

Over a dozen researchers who were interviewed by The Associated Press have said that the marsh in the bay, as well as all along the coast of Louisiana, has begun to heal itself. This gives rise to the hope that the delicate wetlands might just pull through what is said to be the worst offshore oil spill in the history of the United States. Some marshland might just need to be written off, however the losses from the spill will seem laughable when compared to the large losses on the coast every year attributed to normal human development.

This past Tuesday, a small voyage through the Barataria Bay marsh revealed that there were thin shoots growing up through the mass of oily grasses. In other areas, there were still dead mangrove shrubs, no doubt killed by the oil, however even they showed signs of growth.

“These are areas that were black with oil,” explained, a temporary worker with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Matt Boasso.

It’s nice to know that when push comes to shove, mother nature still has a lot of shove left in her, and she won’t be letting a little thing like an oil spill get in the way of our planet’s ecology.

Why the Cries That BP Made the Worst Oil Spill in U.S. History, May Just Be Most Cynical Spin Campaign

The light blue-green sea is so clear, you can see the sun gleam off the silver colored fish frolicking around..

Sounds nice doesn’t it? This is the scene at the Pensacola Beach, on the Gulf Coast of Florida.. But there is one thing missing… Where are all the tourists?

Normally, at this time of year, you would be hard pressed to get even standing room on the beach, but now the beach is almost like one of those private oasis’ you hear about on TV.

So, why are the tourists staying away? It all boils down to one chaotic day last June.. This was the day the Obama administration made the announcement that the BP oil spill was “the worst environmental disaster America has ever faced.” Well you know what happens next. News Networks from all over raced on down to the Pensacola Beach and quickly found what they were seeking – atrocious images of the famous white sandy beaches, smothered with gruesome black ooze, and apparently in dire straights.

This apocalyptic message was strengthened when interviews were conducted with locals of the area. “It’s damn near biblical. This place is done for!” commented Kevin Reed, a 36 year old man, whose family has had the pleasure of swimming and sunbathing in the area for years and years.

His sadness was entirely understandable.

Yet, as has been witnessed this past week, not only is the beach not “done for”, the exact opposite seems to be the truth. Not only that, but had the news crews bothered to go back just three short days after they originally raced down to the beach in the first place, they would have noticed that the black goo had already been removed by a group of the large team BP had put together to clean up the mess.

Now, the BP workers are still on site – however, they are using small instruments to sift out the tiniest particles of oil.

However, a nice clean beach after a “catastrophic” oil spill, doesn’t make for good news does it? I mean who wants to listen to that?

Not the compensation claimants and their sharks, not the politicians, and not even the green lobby tub-thumpers.

So, the going theory is that they made the whole thing up, to help bolster Obama’s image, and get the attention off things that were mainstream news not too long ago.. Remember the story that Obama was using a Fake Social Security Number? How about the other dirt that was brought into the light? True or not, those stories were very damaging to not only Obama, but to the administration as well..

So what better way than to have a “catastrophe” and then have Obama come out the hero?

You will of course need to draw your own conclusions.. But there are a lot of people who finds this scenario a bit fishy… We here at AC are happy just to conclude that it has been a disaster in its own right and see no need to quantify it.

Oil Spill Stopped, Yet More Birds than Ever are Greased up and Ready to Go

It has been over 3 weeks since BP has capped its spewing oil well. The skimming operations to help clean up the mess have all but ground to a halt, and researchers are saying that less than a third of the oil remains in the Gulf of Mexico.

That being the case, wildlife officials are finding more birds covered in the black sticky substance than ever. Fledgling birds are getting stuck in the viscous goo that is left behind after the cleanup efforts have passed on. Rescue workers are making initial visits to the rookeries they had initially avoided, lest they disturb the precious creatures during their nesting time.

What is really disturbing, is that before BP capped off their well on the 15th of July, an average of 37 birds were being pulled in dead or alive each day. Now, after the fact, that figure has doubled up to 71 per day. This information comes to us courtesy of a Times-Picayune review of the daily wildlife rescue reports.

The number of sea turtles discovered is even higher, with more of the poor things covered in the sticky black stuff being found in the last 10 days, than during the disaster’s first three months.

While the increase of oily turtles being found is still stumping researchers, the wildlife officials have said there are several things that could be contributing to the increase in the number of oiled birds being found since the leak was stopped.

Whatever the reasons, something has to be done about the situation, however, no efforts are being focused on that at this point in time.

The Gulf Dead Zone, Might Just Be the Largest Dead Zone on Record!

The “Dead Zone”, the low-oxygen area in the Gulf of Mexico, which has been recorded this year, might just be the largest on record and it overlaps areas which were affected by the oil spill courtesy of our Eco-friendly oil conglomerate BP.

The areas afflicted with low levels of oxygen, also known as hypoxia, cover an area estimated to be over 7,000 square miles of the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico and extended as far as to actually enter Texas waters. This astonishing discovery was made by researchers at the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, after performing a survey of the waters.

The area covered is expected to have included a section off of Galveston, Texas, as well, however poor weather conditions forced the researchers to cut their surveying trip short.

“The total area probably would have been the largest if we had enough time to completely map the western part,” said the consortium’s executive director, Nancy Rabalais.

The largest dead zone that was ever measured in a survey, which started on a regular basis in 1985, was slightly more than 8,000 square miles, and was recorded in 2001.

This annual summer “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico is generally attributed to chemicals used by farmers, and which make their way to the Gulf by means of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers.

The phosphorous and nitrogen contained in agricultural runoffs provide a food source which allows algae to prosper in the Gulf.

When bits of algae die off, or are excreted by sea animals which eat them settle onto the bottom of the water, they decompose and the bacteria consume the oxygen in the water.

The end result, the scientists explained, is that this causes oxygen depletion in the water, which forces many marine animals including fish, shrimp and crabs to either vacate their homes, or suffocate.

The marine life which makes its home in the sediments can survive with relatively little oxygen, however they will begin to die off as the oxygen level approaches zero.

To be considered as part of this “Dead Zone”, the oxygen levels in bottom waters in the Gulf of Mexico need to be at a level of 2 parts per million or less.

By the end of July this year, large areas of the norther part of the Gulf of Mexico had already reached that level, including one part close to Galveston Bay.

The area which the BP oil spill overlaps in some areas in the “Dead Zone”, Rabalais explained, and microbes which would be used to help clean up the spill can deplete oxygen levels in the water.

Be that as it may, scientists could not say that there is a definite link between the devastating oil spill, and the size of the “Dead Zone”.

“It would be difficult to link conditions seen this summer with oil from the BP spill in either a positive or negative way,” Rabalais explained.

It’s the Oil We Can’t See in The Gulf That Poses Great Risk!

Government officials have gone on the record, and stated that the spill in the Gulf of Mexico is no longer a threat to the East Coast, however Marine Scientists are begging to differ. The scientists are saying it’s not the oil we can see, but the oil that we can’t see, that is the problem.

The marine scientists are shouting out against the government claims that the oil spill in the Gulf is finally being taken care of, and no longer is putting Florida, or the rest of the East Coast at risk. The scientists firmly believe that the oil may simply have moved itself to under the water, and as such still poses an immense risk to fish and other sea lifeforms.

“Just because you don’t see it on the surface or on the coast, it doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem,” explains the director of the coastal marine laboratory at Florida State University, Felicia Coleman,

“I want to know what’s happening with dispersants and dispersed oil. If there are large plumes of oil underwater we might not be able to see for some time “

On the 27th of last month, Jane Lubchenco, administrator of the NOAA, released the following statement; “the coast remains clear” for the Eastern Seaboard.

“With the flow stopped and the loop current a considerable distance away, the light sheen remaining on the Gulf’s surface will continue to biodegrade and disperse, but will not travel far,” Lubchenco explained.

However, others feel, that if the oil has made its way underwater, it could be quite some time before we know the whole story, and what impact it could have on the delicate ecosystems around the world.