Tag Archives: Florida

Scientists find huge smelly blob in Florida waters

Scientists researching the Gulf of Mexico have found an underwater mass of dead biological material that appears to be growing as microscopic algae and bacteria get trapped and die. The blob is at least three feet (90 cm) thick and spans two-thirds of a mile (1 mile = 1 609 meters) parallel to the coast just off the Florida Panhandle, within the site of Perdido Key. The blob smells like rotten eggs and feels similar to jelly.

The researchers have been unable to determine how the blob was formed, where it comes from or where it will go. Tests show that the material is nearly 100% biological and less than a year old. It is also clear that tiny organisms have gotten stuck in the sticky blob and died. Tests carried out by the researchers also showed that the blob has no connection to land.

“It seems to be a combination of algae and bacteria,” says David Hollander, a chemical oceanographer with the University of South Florida. According to Hollander, the substance is toxic and “extraordinarily sticky”.

Scientists are not ruling out a connection to last years’ Deepwater Horizon disaster, but so far none of the tests have shown any sign of oil.

Researchers encountered the blob for the first time in December as they were searching for oily sediments on the sea floor. They did find such sediments, but they also got a tip about something weird floating around roughly half a mile from Perdido Pass and this caused them to change their plans and head over to the area to investigate.

The environment where the blob can be found is a relatively pristine sloping shelf. Normally, wave action will sweep away any sediments here.

Hollander and his team are planning to return to the blob within a few weeks to gather more samples, since they were unable to get any material from the bottom of the blob during their last visit. They will also try to map out the entire blob to be able to see exactly how big it is.

Scientists use sedation to free young entangled Right Whale

Scientists from NOAA and its state and nonprofit partners have applied at-sea chemical sedation to successfully free a young North Atlantic Right Whale off the coast of Cape Canaveral in Florida, USA.

This is only the second time a free-swimming whale has been successfully sedated to enable disentanglement. The first case also concerned a whale spotted off the coast of Florida and occurred in March 2009.

In the most recent case, a female Right Whale born during the 2008-2009 calving season had roughly 200 feet (60 meters) of rope wrapped through her mouth and around the flippers when an aerial survey team spotted her on December 25. Five days later a disentanglement team from Georgia Department of Natural Resources and Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission was able to remove about 150 feet (45 meters) of rope from her. Unfortunately, they couldn’t safely get the rest of the rope off her and this is why NOAA decided to sedate her, after having tracked her via satellite tag for half a month to see if the remaining rope would come off on its own.

“Our recent progress with chemical sedation is important because it’s less stressful for the animal, and minimizes the amount of time spent working on these animals while maximizing the effectiveness of disentanglement operations,” says Jamison Smith, Atlantic Large Whale Disentanglement Coordinator for NOAA’s Fisheries Service. “This disentanglement was especially complex, but proved successful due to the detailed planning and collective expertise of the many response partners involved.”

On January 15, researchers deemed that the Right Whale wouldn’t be able to free herself from the remaining 50 feet (15 meters) of rope without assistance. The weather was favorable for a rescue mission and a disentanglement team comprised of scientists from NOAA, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, University of Florida, EcoHealth Alliance , and Coastwise Consulting (was dispatched into the Atlantic. Back on shore, the Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies and the New England Aquarium got ready to provide off-site assistance.

The entangled Right Whale was fitted with a temporary satellite tag that would record her behavior before, during and after sedation. She was then sedated and had ropes as well as mesh material removed from her. The mesh resembled mesh used to catch fish, crabs and lobsters along the Atlantic coast and NOAA’s Fisheries Service is currently examining it in an effort to determine its geographic origin.

Once the whale had been freed from the garbage, the researchers administered a drug that reversed the sedation. The whale also received some antibiotics to threat the wounds caused by the debris. She will now be tracked for up to 30-days through the temporary satellite tag.

If you see an entangled or otherwise injured whale you are encouraged to report it to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (1-888-404-FWCC or 1-888-404-3922) or the Georgia Department of Natural Resources (1-800-2-SAVE-ME or 1-800-272-8366).

Cold Spell in Florida Kills 699 Manatees in 2010: “Warm Water Sites” in Dire Need

The cold spells experienced earlier on in the year have resulted in the record for killed manatees in 2010. Since the beginning of the year, up until the 5th of December, researchers with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s Fish and Wildlife Research Institute has counted a staggering 699 dead manatees floating about in state waters.

This number of deaths is double the average of killed manatees over the past half decade.

It was quite a shock to see so many cold related manatee deaths this year. What’s more astonishing that the number, is how far it was spread out. It spread throughout much of the State of Florida to as far south as the Everglades and even the Florida Keys – which aren’t normally known for cold related deaths of manatees.

Even though this cold spell was natural, the number of manatee deaths has drawn attention to the fact that warmer waters are needed for the species to pull through.

“We are very concerned about the unusually high number of manatee deaths this year. Data from our monitoring programs over the next few years will tell us if there are long-term implications for the population,” explains Gil McRae, the director of FWRI.”The cold-related deaths this past winter emphasize the importance of warm-water habitat to Florida’s manatees. Maximizing access for manatees to natural warm-water sites will continue to be a focus for the FWC and our partners moving forward.”

While there hasn’t been any forthcoming suggestions, there will be more research done into the matter and a solution proposed, hopefully sooner rather than later.

Mother-Daughter Dive Team Discover Golden Bird Valued at Over $800,000

Bonnie Schubert, along with her eighty-seven year old mother, have been scouring the coast of Florida for decades in the search of treasure.

In a common day they will burrow up to a dozen times, dive deep into murky water, and wind up with a beer can or fishing lure for their efforts.

“I spent a whole season and only came up with a musket ball,” explains Bonnie.

However, on one such excursion this past August, the Schuberts were searching near Frederick Douglass Beach when they hit the motherlode.

“The first thing that came into focus was the head of the bird and the wing…and it was something I never imagined…just didn’t expect at all..” Bonnie recalls.

What they had stumbled upon was a 22-carat solid gold bird, a find they thing may date back to 1715, as part of a cargo of a lost Spanish ship. This Spanish fleet, which wrecked close to Fort Pierce, is believed to have dumped millions of dollars of gold and jewels all along the bottom.

“It’s truly been amazing. It’s not something we could have ever predicted,” commented a principal with 1715 Fleet-Queen’s Jewels, LLC, the corporation that holds the rights to treasure hunting in the region, Brent Brisbane.

While the Schuberts obviously have a claim, however the State may wish to have the bird, leading to some “treasure trading” to make things right. However, there is no doubt that this mother-daughter dive team has found the find of their lifetime.

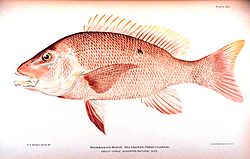

Despite Oil Spill, Fish Fry Showing up In Record Numbers in Gulf of Mexico

Snapper fry are all over the place. There are also trout, grunt and grouper fry all over the place as well. The early tabulation of the annual count in the beds of grass spattered about the northern part of the Gulf of Mexico seems to suggest that the larvae of some kinds of fish have survived the BP oil fiasco, and what’s more, there are swarms of them.

“My preliminary assessment, it looks good, it looks like we dodged a bullet. In terms of the numbers of baby snapper and other species present in the grass beds, things look right,” commented a scientist with the University of North Carolina’s Institute of Marine Science, Joel Fodrie, who has been actively involved in the study of seagrass meadows along the coast for the past five years.

Joel’s group has taken samples of the different sea life in the grass beds in Alabama, Mississippi, and the Florida Panhandle. They will be taking a sample from around Louisiana’s Chandeleur Islands come this Autumn.

Back at the height of the fiasco, when a seemingly endless stream of oil was floating about on the surface, researchers were most concerned as to whether the trillions of larvae which hatch each spring offshore would survive the severe contamination of the spill.

It’s looking like they did, and it’s a good thing too. It just goes to show you that mother nature is more resilient than we give her credit for. There is hope yet for the Gulf to make a full recovery, and that folks, is good news indeed.

Nursery Grown Corals to be Planted On Forida Keys Reef:

The only living coral reef in North America has really been put through a lot by humans, with the hellish effects of a booming population on mainland Florida as well as in the Keys, which is causing some coral to die and a lot of others to become distressed. Researcher are now focusing on a way to try and help repair the damage done, and even restore the reef to its previous glory.

Researchers have been raising coral, which is still a living organism, in nurseries so that it can be easily moved into the ocean, with a minimum of fuss and muss. The plan is to begin with Davis Reef in Islamorada (purple island), which has been particularly hard done by, thanks to growth, shipping, and other man made messes.

Bill Sharp, a researcher over at Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, has explained that the work to be performed on Davis Reef could aid scientists in better understanding how nursery-grown coral can come to the aid of natural coral.

Researchers also hope that the project will help bring back the long-spined sea urchins, which normally use the coral reefs for shelter.

Not only does the reef provide shelter for a myriad of life in the sea, living reefs are also a major draw in terms of tourism, attracting divers and snorkelers from all over the place, year in and year out.

If the reef could somehow have the damage done to it repaired, and the age of the dam is not too much, then coral reefs can regenerate over time, however it can take decades, hundreds or even thousands of years to replenish to their natural states

Rare Corals Being Cultivated in Offshore Nurseries to Help Depleted Reefs

An accidental find just off of Key Largo has lead to farms being created for delicate, yet ever so important, species of coral.

Just over 30 feet below the calm waters above the colorful reef off of Key Largo, Ken Nedimyer proudly displays a small slate which reads “Let’s plant corals.”

Along with a team of volunteer divers, they quickly get to work and utilize epoxy putty to help tiny bits of staghorn coral gain a foothold in the great big ocean.

In the vast expanse of ocean just off of Key Largo, Fort Lauderdale, and a few other choice locations, Nedimyer, an accomplished collector of tropical fish from Tavernier, along with researchers and his hodgepodge group of volunteers, are getting to work and raising groups of rare coral species to help repopulate the rapidly depleting reefs of the southeastern United States.

“These are my little children,” 54 year old Nedimyer, commented later that same day, explaining that the endangered coral which he has been cultivating on slabs of concrete, grows much like delicate saplings in an aquatic underwater offshore nursery.

Elkhorn and staghorn corals are classified as undersea architects, they create structures in the reef which then in turn support a myriad of sea lifeforms such as sponges, fish, lobsters, and many others. These reefs have really taken a beating from things like global warming, disease, and many other stresses over the past three decades, and have declined to just a few sparse patches in the warm waters that run from southern Palm Beach County to the islands of the Caribbean.

However, in an exciting turn of events, staghorn coral was found growing in an undersea farm for commercial aquarium rock, and researchers have now begun to raise these diffent species of coral in nurseries located offshore with the ultimate goal of transplanting them back into the wild.

The Obama administration, through economic stimulus money, has been financing the expansion of the $3.4 million project. It is hoped that this will create 57 full time jobs, commented Tom Moore, who is a representative of the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration’s Habitat Restoration Center in St. Petersburg.

Healthy reefs lead to more jobs in the tourism industry, increase the habitat for fisheries, and even provide much needed protection from weather patterns such as hurricanes, Moore continued.

Today there are now a row of 10 such coral nurseries which stretch from Fort Lauderdale to the U.S. Virgin islands, which are cultivating new stands of both the elkhorn and staghorn coral.

“These are two of the most important species of coral,” explained the marine science program manager for The Nature Conservancy, James Byrne. The Nature Conservancy is an ecologically minded group of individuals corporations that have applied for the federal money and is coordinating the work. “The staghorn coral provides very important habitat for juvenile fish, and elkhorn coral is one of the most important reef builders.”

It is nice to see that a group has taken an interest in the “reforestation” of the seas, as well as on land. The ocean is crucial to our world’s survival.. Nice to know someone has remembered that.

It’s the Oil We Can’t See in The Gulf That Poses Great Risk!

Government officials have gone on the record, and stated that the spill in the Gulf of Mexico is no longer a threat to the East Coast, however Marine Scientists are begging to differ. The scientists are saying it’s not the oil we can see, but the oil that we can’t see, that is the problem.

The marine scientists are shouting out against the government claims that the oil spill in the Gulf is finally being taken care of, and no longer is putting Florida, or the rest of the East Coast at risk. The scientists firmly believe that the oil may simply have moved itself to under the water, and as such still poses an immense risk to fish and other sea lifeforms.

“Just because you don’t see it on the surface or on the coast, it doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem,” explains the director of the coastal marine laboratory at Florida State University, Felicia Coleman,

“I want to know what’s happening with dispersants and dispersed oil. If there are large plumes of oil underwater we might not be able to see for some time “

On the 27th of last month, Jane Lubchenco, administrator of the NOAA, released the following statement; “the coast remains clear” for the Eastern Seaboard.

“With the flow stopped and the loop current a considerable distance away, the light sheen remaining on the Gulf’s surface will continue to biodegrade and disperse, but will not travel far,” Lubchenco explained.

However, others feel, that if the oil has made its way underwater, it could be quite some time before we know the whole story, and what impact it could have on the delicate ecosystems around the world.

Lionfish Have Been Discovered in the Gulf of Mexico, Just Off Southwest Florida!

They are poisonous, alien, and they have just been discovered (yet again) a little too close for comfort, in the Gulf of Mexico just off the shores of Southwest Florida.

Two young lionfish have been reeled in by Florida fisheries scientists this past week by two different fishing expeditions, one 99 miles from the coast, and the other 160 miles off the coast, just a tad north of the Dry Tortugas, and a little bit west of Cape Romano. This news was reported by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research institute in a conference.

This is the first time that lionfish have been discovered in Gulf waters north of the Tortugas and the Yucatan Peninsula.

Researchers have said that these lionfish were the product of either a spawning population on the West Florida continental shelf, or ,and everyone is hoping for this explanation, that the lionfish were carried there by ocean currents from other spawning areas.

Whatever the reason, this just might mean that the lionfish are spreading out in the eastern Gulf, scientists have cautioned.

These particular lionfish, which were measured to be in the neihborhood of 2 and a half inches long, were discovered at 183 feet and 240 feet below the seemingly calm waters of the area.

Before they were reeled in last week, lionfish had been spotted in the Tampa Bay area, Atlantic coastal waters, and even in the Florida Keys and Dry Tortugas.

What makes this so interesting is that the lionfish generally makes its home in the reefs and other rocky crevices of the Indo-Pacific, explains the Fish and Wildlife Research Institute.

Divers Beware!! Lionfish Invasion in Miami’s Inshore Waters!!

Key Biscayne, Florida – It appears that Lionfish are soon going to be a very common thing in the shallower waters off the coast of Miami. A young Lionfish was captured just off of the Key Biscayne beach this past Saturday, it is only one of five of this invasive species spotted within the last few weeks.

The Lionfish generally makes its home in the Pacific Ocean, and they are known to breed quickly, and often have voracious appetites. This means that these invading Lionfish could possibly throw the whole marine ecosystem of South Florida out of whack by them eating up baby lobsters, groupers and other species native to the reef.

The mere fact that they are present could spell trouble for this years’ lobster season, as Lionfish and lobsters have the same tastes in habitats, which include underwater crevices and holes, and they are known to be highly toxic. They are equipped with a multitude of tiny poison tipped spines, and can give you quite a nasty sting.

Steven Lutz, a local snorkeling enthusiast, managed to catch himself a baby Lionfish on Saturday while in the company of Dr. Michael Schmale, from the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School for Marine and Atmospheric Science. Scientists are able to pinpoint where these Lionfish come from by running genetic tests. “I have been swimming these waters for the past twenty years and this is the first time we have seen them here,” Lutz informed, “Divers should use extra caution when grabbing for a lobster this season, or they might be in for a nasty and painful surprise.”