Tag Archives: Fish

Vandenberg sunk in 1 minute and 54 seconds

As reported earlier here and here, the retired 523-foot military vessel “Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenberg” was scheduled to be sunk this month to become an artificial reef off the Floridian coast, and we can now happily report that everything has gone according to plan.

After being slightly delayed last minute by a sea turtle venturing into the sinking zone, Vandenberg was successfully put to rest roughly 7 miles south-southeast of Key West at 10:24 a.m., May 27.

Once 44 carefully positioned explosive charges had been detonated, Vandenberg gracefully slipped below the water’s surface in no more than 1 minute and 54 seconds. It is now resting rightside-up on the sea bottom at a depth of roughly 140 feet (43 metres) in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

Divers and other underwater specialists are currently surveying the ship to make sure it is safe for the public to explore. Hopefully, Vandenberg will open up for public diving by Friday morning.

Over 20 cameras were mounted on the vessel to capture images of it descending into the blue, cameras that are now being retrieved by an underwater team.

Vandenberg is the second largest vessel ever intentionally sunk to become an artificial reef. In 2006, the 888-foot long USS Oriskany, also known as CV-34, was sunk in the Gulf of Mexico, south of Pensacola, Florida.

Stingray mass death in U.S. Zoo

Eleven of the 18 freshwater stingrays living at the U.S. National Zoo died over the holiday weekened, together with two arowanas. All dead fishes were residents of the zoo’s Amazonia exhibit; a 55,000-gallon (208,000 L) aquarium designed to replicate a flooded Amazon forest. Zoo officials are now suspecting low oxygen levels to be behind the sudden mass death.

Picture of Motoro Sting Ray, Ocellate river stingray – Potamotrygon motoro. Not one of the dead rays.

Copyright www.jjphoto.dk

As soon as the deaths were discovered 7 a.m Monday morning, zookeepers tested the water and found low levels of dissolved oxygen. They immediately started supplementing the aquarium with reservoir water and no more fish have died so far. In addition to stingrays and arrowanas, the Amazon aquarium is also home to discus, boulengerella fish, and a large school of guppies. By 10:15 a.m. Monday, the oxygen levels were back to normal but zookeepers continue to monitor the health of the surviving fish just in case.

Necropsies performed on the dead fish did not unveil any definite cause of death, which makes low oxygen levels even more likely, according to National Zoo officials. They do not believe human error caused the oxygen drop, since all protocols and checks were properly followed Sunday night.

Insufficient levels of dissolved oxygen in the water are one of the most common causes of fish mass death, in the wild as well as in captivity. Last year, 41 stingrays died at the Calgary Zoo in Canada due oxygen scarcity in the water.

Shark-Free Marinas

Brooks is a scientific advisor for the not-for-profit Company Shark-Free Marina Initiative, SFMI, who has just instigated a new strategy for preventing the deaths of millions of sharks belonging to vulnerable or endangered species.

The Shark-Free Marina Initiative works by prohibiting the landing of any caught shark at a participating marina. The initiative is based on the Atlantic billfish model which banned the mortal take of billfish in the 1980’s to give severely depleted populations a chance to recover.

By promoting catch-and-release and working closely with marinas and game fishing societies, SFMI hopes to win over the fishing community. Other important allies in the endeavour are competition sponsors and tackle producers.

Collaborating with the Fisheries Conservation Foundation in the USA and the Cape Eleuthera Institute in the Bahamas, SFMI has already gained the attention of marinas and non-profits nation-wide.

Enlisting the aid of anglers

By practising catch-and-release, sport fishers can not only decrease their impact on shark species; they can also actively aid ongoing research studies by collecting valuable data.

“Although the number of sharks killed by recreational fishermen each year is dwarfed by commercial catches, the current crisis facing shark stocks requires action wherever possible.” says Brooks.

During the last five years, the average number of sharks harvested annually by sport- and recreational anglers in the United States exceeded half a million. The outlook for these shark populations seem even graver when you take into account that many of the sharks targeted by fishermen are large, breeding age specimens belonging to endangered or vulnerable species. Removing so many sexually mature specimens from a population each year naturally has a major impact on its chances of long-term survival.

“Shark-Free Marinas is a necessary response to the culture of mature shark harvest” says SFMI’s Board Director, Marine Biologist Luke Tipple “Our effect will be immediate, measurable and, together with saving millions of sharks, will establish a new global standard for responsible ocean management. There’s a lot of talk about the atrocity of shark fining and fishing worldwide, but not a lot of measurable action towards reversing the damage. The time has come to stop simply ‘raising awareness’ and start implementing sensible management techniques to protect vulnerable species of sharks from inevitable destruction.”

You can find more information at www.sharkfreemarinas.com.

Help the project!

To explore strange new worlds; to boldly go into the plastic vortex

The expedition, headed by Hong Kong based entrepreneur and conservationist Doug Woodring, hopes to learn more about the nature of the vortex and investigate if it is possible to fish out the debris without causing even more harm.

“It will take many years to understand and fix the problem,” says Jim Dufour, a senior engineer at Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California, who is advising the trip.

According to Dufour, research expeditions like this one are of imperative importance since establishing the extent of the problem is vital for the future health of the oceans.

“It [the expedition] will be the first scientific endeavour studying sea surface pollutants, impact to organisms at intermediate depths, bottom sediments, and the impacts to organisms caused by the leaching of chemical constituents in discarded plastic,” he says.

The research crew, which will pass through the gyre twice on their 50-day journey from San Francisco to Hawaii and back, are using a 150-foot-tall (45-metre-tall) ship – the Kaisei, which is Japanese for Ocean Planet. They will also be accompanied by a fishing trawler responsible for testing various methods of catching the garbage without causing too much harm to marine life.

“You have to have netting that is small enough to catch a lot but big enough to let plankton go through it,” Woodring explains.

Last year, building contractor and scuba dive instructor Richard Owen formed the Environmental Cleanup Coalition (ECC) to address the issue of the pollution of the North Pacific. A plan designed by the coalition suggests modifying a fleet of ships to clear the area of debris and form a restoration and recycling laboratory called Gyre Island.

Hopefully, the garbage can not only be fished up but also recycled or used to create fuel, but a long term solution must naturally involve preventing the garbage from ending up there in the first place.

”The real fix is back on land. We need to provide the means, globally, to care for our disposable waste,” says Dufour.

Despite being sponsored by the water company Brita and backed by the United Nations Environment Programme, the expedition is still looking for more funding to meet its two million US dollar budget. Since the enormous trash pile is located in international waters, no single government feels responsible for cleaning it up or funding research. Another problem is lack of awareness; since very few people ever even come close to this remote part of the ocean it is difficult to make the problem a high priority issue. A documentary will be filmed during the expedition in hope of making the public more aware of where the world’s largest garbage dump is actually located.

What is the Eastern Garbage Patch?

According to data from the United Nations Environment Programme, our oceans contain roughly 13,000 pieces of plastic litter per square kilometre of sea. However, this trash is not evenly spread throughout the marine environment – spiralling ocean currents located in five different parts of the world are continuously sucking in vast amounts of litter and trapping it there. Of these five different gyres, the most littered one is located in the North Pacific – the Eastern Garbage Patch.

The five major oceanic gyres.

The existence of the Eastern Garbage Patch was first predicted in a 1988 paper published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the United States. NOAA based their prediction on data obtained from Alaskan research carried out in the mid 1980s; research which unveiled high concentrations of marine debris accumulating in regions governed by particular patterns of ocean currents. Using information from the Sea of Japan, the researchers postulated that trash accumulations would occur in other similar parts of the Pacific Ocean where prevailing currents were favourable to the formation of comparatively stable bodies of water. They specifically indicated the North Pacific Gyre.

California-based sea captain and ocean researcher Charles Moore confirmed the existence of a garbage patch in the North Pacific after returning home through the North Pacific Gyre after competing in the Transpac sailing race. Moore contacted oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmeyer who dubbed the region “the Eastern Garbage Patch” (EGP).

Twice the size of Texas

The Eastern Garbage Patch is located roughly 135° to 155°W and 35° to 42°N between Hawaii and mainland USA and is estimated to have grown to twice the size of Texas, even though no one knows for sure exactly how large the littered area really is. The garbage patch consists mainly of suspended plastic products that, after spending a long time in the ocean being broken down by the sun’s rays, have disintegrated into fragments so miniscule that most of the patch cannot be detected using satellite imaging.

Impact on wild-life and humans

The plastic soup resembles a congregation of zooplankton and is therefore devoured by animals that feed on zooplankton, such as jellyfish. The plastics will then commence their journey through the food chain until they end up in the stomachs of larger animals, such as sea turtles and marine birds. When ingested, plastic fragments can choke the unfortunate animal or block its digestive tract.

Plastics are not only dangerous in themselves, they are also known to absorb pollutants from the water, including DDT, PCB and PAHs, which can lead to acute poisoning or disrupt the hormonal system of animals that ingest them. This is naturally bad news for anyone who likes to eat marine fish and other types of sea food.

Discarding fish at sea may be banned, EU officials say

“What’s the point of setting a quota if fishermen aren’t accountable for the fish they actually catch?” says Mogens Schou, a Danish fishery official.

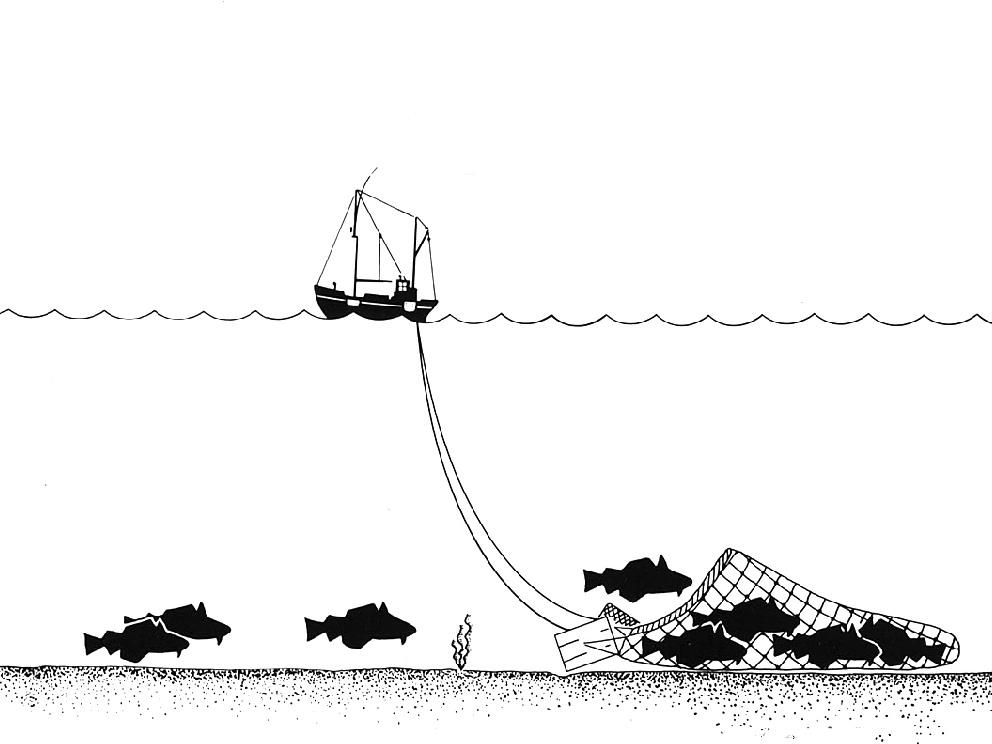

The EU’s quotas limit the size of the annual catch that countries and their fleets can sell on their return to harbour, but instead of protecting remaining fishing populations from depletion, the system is making fishermen dump lower-value fish at sea to maximize profit. According to officials in the European Commission’s fisheries office, most of these fishes do not survive.

“To stay under their quotas, and make more money, fishermen discard half of what they catch,” says Schou, “They ‘high-grade’ – in other words, only keep the most profitable fish.”

Last month, an EU report was released highlighting the failure of current EU fishing regulations by showing that 88% of fish species in EU waters are being fished out faster than they can reproduce. In response to the report, fishery ministers from the 27 EU nations are currently discussing how to protect the remaining fish stocks from complete eradication.

As a part of these talks, Denmark has proposed an amended quota system where fishermen and their countries are held accountable for the amount of fish caught rather than the amount returned to port. To make it harder for fishing fleets to cheat, Denmark is also proposing that fishermen voluntarily equip their boats with on-board cameras. In exchange, the fishermen would get bigger quotas.

Denmark has already designed a surveillance kit consisting of four cameras, a GPS (Global Positioning System) device, and sensors that notice when fish is being hauled or dumped. The Danish kits are currently being used on six fishing boats with Danish officials monitoring the footage.

Danish fisherman Per Nielsen installed the kit on his trawler Kingfisher in September and believes it to be a good investment. The kit cost roughly 10,000 USD, but Nielsen was compensated by being allowed to catch several extra tens of thousands of dollars worth of cod.

As of now, EU fishermen throw overboard an estimated 50% of the fish they catch and did for instance dump 38% of the 24,000 tons of cod they caught last year, according to the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea.

Stirring, charging, and picking: hunting tactics of Brazilian stingrays

If you want to learn more about how the charismatic creatures known as stingrays feed, you should check out a new study published in the most recent issue of Neotropical Ichthyology.

While spending days and nights scuba diving and snorkelling in the upper Paraná River of Brazil, researchers Domingos Garrone-Neto and Ivan Sazima made 132 observations of freshwater stingrays and noticed three different forms of foraging behaviour.

Picture of Motoro Sting Ray, Ocellate river stingray – Potamotrygon motoro.

Copyright www.jjphoto.dk

The first hunting technique involved hovering close to the bottom, or even settle on top of it, while undulating the disc margins. By doing so, the stingray would stir up the substrate, unveiling small invertebrates. The invertebrates – typically snails, crabs and larval insects – could not escape from under the ray’s disc and ended up as food.

When using its second hunting technique, the stingray would slowly approach shallow water while keeping its eyes on suitable prey items that concentrate in such environments. When it got close enough, it would make a rapid attack; stunning the prey or trapping it under its disc. This hunting technique did not target tiny invertebrates hiding in the sand; it focused on tetras and freshwater shrimps instead. The studied stingrays only used this method during the night when they could sneak up on prey without being seen.

The third technique observed relied on the presence of vertical or inclined surfaces in the water, such as boulders and tree stumps, including man-made structures like concrete slabs. On this type of objects a lot of different organisms, e.g. snails, like to crawl around or attach themselves. The hunter would simply position itself with the anterior part of its disc above the water’s edge and start picking the animals off the surface, one at a time.

The two studied species were Potamotrygon falkneri and Potamotrygon motoro; both belonging to a genus of freshwater stingrays found exclusively in South America.

As mentioned above, you can find the paper in Neotropical Ichthyology 7.

Garrone-Neto, D and I Sazima (2009) Stirring, charging, and picking:

hunting tactics of potamotrygonid rays in the upper Paraná River. Neotropical Ichthyology 7, pp. 113–116.

55 percent of coral reefs in South Sulawesi damaged by explosives

Around 55 percent of coral reefs in South Sulawesi waters have been damaged by destructive fishing practices, the South Sulawesi marine and fishery service announced on Wednesday. Due to the destructive practise of throwing explosives into the water to catch fish, only 45 percent of the coral reefs in the national marine park of Takabonerate are in good condition.

The Indonesian Naval personal have arrested fishermen in South Sulawesi for using explosives to catch fish, but the practise continues.

Takabonerate is considered the world`s third most beautiful marine park and has received an award from the World Ocean Conference (WOC) which was held in Manado, North Sulawesi, this month. This marine park is located within the famous Coral Triangle; a Pacific region home to over 75 percent of the world’s known coral species. This figure becomes even more remarkable if you take into account that the triangle only comprises two percent of the world’s ocean.

Hopefully, the situation in the region will improve as six heads of state/government participating in the Coral Triangle Initiative (CTI) Summit organized as part of the WOC signed a declaration on May 15, approving the Coral Triangle Initiative Program. Within this program, the six countries who share this amazingly coral rich region will coordinate their protection of marine resources.

Over 120 million people depend on the Coral Triangle ecosystem for their survival and would suffer greatly if the diversity of fish, shellfish and other marine creatures were to become depleted due to unsustainable fishing practises.

Are fish getting increasingly suspicious of hooks?

The inclination to end up stuck on a hook seems to be a heritable trait in bass, according to a study published in a recent issue of the Transactions of the American Fisheries Society.

The study, which was carried out by researchers DP Philipp, SJ Cooke, JE Claussen, JB Koppelman, CD Suski, and DP Burkett, focused on Ridge Lake, an Illinois lake where catch-and-release fishing has been enforced and strictly regulated for decades. Each caught fish has been measured, tagged and then released back into the wild.

Picture by: Clinton & Charles Robertson from Del Rio, Texas & San Marcos, TX, USA

David Philipp and coauthors commenced their study in 1977, checking the prevalence of Largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) on the hooks of fishermen. After four years, the experimental lake was drained and 1,785 fish were collected. When checking the tags, Philipp and his team found that roughly 15 percent of the Largemouth bass population consisted of specimens that had never been caught. They also found out that certain other bass specimens had been caught over and over again.

To take the study one step further, the research team collected never caught bass specimens (so called Low Vulnerability, LV, specimens) and raised a line of LV offspring in separate brood ponds. Likewise, the team collected bass specimens caught at least four times (High Vulnerability, HV, specimens) and placed them in their own brooding ponds to create a HV line.

The first generation (F1) offspring from both lines where then marked and placed together in the same pond. During the summer season, anglers where allowed to visit the pond and practise catch-and-release, and records where kept of the number of times each fish was caught.

As the summer came to an end, HV fish caught three or more times where used to create a new line of HV offspring, while LV fish caught no more than once became the parents of a new LV line.

The second generation (F2) offspring went through the same procedure as their parents; they were market, released into the same pond, and subjected to anglers throughout the summer. In fall, scientists gathered the fish that had been caught at least three times or no more than once and placed them in separate ponds to create a third generation (F3) HV and LV fish.

A following series of controlled fishing experiments eventually showed that the vulnerability to angling of the HV line was greater than that of the LV line, and that the differences observed between the two lines increased across later generations.

If this is true not only for bass but for other fish species as well, heavy hook-and-line angling pressure in lakes and rivers may cause evolutionary changes in the fish populations found in such lakes. Hence, a lake visited by a lot of anglers each year may eventually develop fish populations highly suspicious of the fishermen’s lure.

More information can be found in the paper published in Transactions of the American Fisheries Society: Philipp, DP, SJ Cooke, JE Claussen, JB Koppelman, CD Suski and

DP Burkett (2009) Selection for vulnerability to angling in Largemouth Bass. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 138, pp. 189–199.

Little time left to save the worlds remaining oyster reefs; 85 percent have already been lost

This one of its kind report is a collaborative work carried out by scientists from five different continents employed by academic and research institutions as well as by conservation organizations.

The report, which focuses primarily on the distribution and condition of native oyster reefs, show that 85 percent of oyster reefs have been completely destroyed worldwide and that this type of environment is the most severely impacted of all marine habitats.

In a majority of individual bays around the globe, the loss exceeds 90 percent and in some areas the loss of oyster reef habitat is over 99 percent. The situation is especially dire in Europe, North America and Australia where oyster reefs are functionally extinct in many areas.

“We’re seeing an unprecedented and alarming

decline in the condition of oyster reefs, a critically

important habitat in the world’s bays and estuaries,”

says Mike Beck, senior marine scientist at The Nature

Conservancy and lead author of the report.

Many of us see oysters as a culinary delight only, but oyster reefs provide us humans with a long row of valuable favours that we rarely think about. Did you for instance known that oyster reefs function as buffers that protect shorelines and prevent coastal marshes from disappearing, which in turn guard people from the consequences of hurricanes and other severe storm surges? Being filter feeders, oysters also help keep the water quality up in the ocean and they also provide food and habitat for many different types of birds, fish and shellfish.

Even though the situation is dismal, there is still time to save the remaining populations and aid the recuperation of damaged oyster reefs. In the United States, millions of young Olympia oysters have been reintroduced to the mudflats surrounding Netarts Bay in Oregon, in an effort to re-create a self-sustaining population of this native species. The project is a joint effort by government and university scientists, conservation groups, industry representatives, and local volunteers.

“With support from the local community and other partners, we’re demonstrating that shellfish restoration really works”, says Dick Vander Schaaf, Oregon director of coast and marine conservation for the Conservancy. “Expanding the effort to other bays and estuaries will help to ensure that the ecological benefits of oyster reefs are there for future generations.”

If wish to learn more about the global oyster reef situation, you can find the report here.

Are trawlers obliterating historic wrecks?

An example of the damage trawlers can cause is the wreck of HMS Victory, a British warship sunk in the English Channel in 1744. Trawling nets and cables have become entangled around cannon and ballast blocks, and three of the ship’s bronze cannons have been displaced. One of them, a 42-pound (19 kg) cannon weighing 4 tonnes, has been dragged 55 metres (180 feet) and flipped upside down. Two other cannon recovered by Odyssey Marine Exploration last year show fresh scratches from trawls and damage caused by friction from nets or cables.

“We know trawlers work the Victory site because one almost ran us down while we were there,” says Tom Dettweiler, senior project manager of Odyssey Marine Exploration.

“It turns out that Victory is right in the middle of the heaviest trawling area in the Western Channel,” says Greg Stemm, chief executive of the company. “We were shocked and surprised by the degree of damage we found in the Channel, he continues. “When we got into this business, like everyone else we thought that beyond 50 or 60 metres, below the reach of divers, we’d find pristine shipwrecks. We thought we’d be finding rainforest, but instead found an industrial site criss-crossed by bulldozers and trucks.”

While surveying 4,725 sq miles (12,300 sq km) of the western Channel, Odyssey Marine Exploration found 267 wrecks, of which 112 showed evidence of being damaged by bottom trawlers. That is over 40 percent.

The English Channel has been a busy area for at least three and half millennia and was thought to be littered with wrecks. In these fairly cold waters, wooden ships tend to stay intact for much longer periods of time than they would in warm tropical regions. Strangely enough, Odyssey Marine Exploration found no more than three pre-1800 wrecks when surveying the area using modern technology sensitive enough to disclose a single amphora. According to historic estimations, at least 1,500 ships have been lost in these waters so finding no more than three pre-1800 wrecks calls for further investigation.

Odyssey Marine Exploration blames bottom trawlers for the lack of wrecks. “The conclusion and fear is that the vast majority of pre-1800 sites have already been completely obliterated by the deep-sea fishing industry,” says Sean Kingsley, of Wreck Watch International, the author of the Odyssey report.

Odyssey Marine Exploration is the world’s only publicly-listed shipwreck exploration company and critics argue that these American treasure hunters are overstating the damage for their own gain.

“You have to ask why Odyssey is doing such a study,” said Robert Yorke, chairman of the Joint Nautical Archaeology Policy Committee. “They want to pressurise the UK Government to allow them to get at the wreck . . . the Victory hasn’t disappeared since 1744; it’s not going to disappear tomorrow.”

The Ministry of Defence has jurisdiction over warships’ remains and it has asked English Heritage for an assessment of the threats to the site. English Heritage has a policy of leaving shipwrecks untouched on the seabed unless a definite risk can be shown.