Tag Archives: boat

Inflatable submarine invented in Gloucestershire

A rigid inflatable boat capable of submerging and operating underwater has been developed by Severn (7) Shipbuilders in Gloucestershire, UK.

The boat is intended for carrying workers and equipment to underwater structures in need of repair or maintenance work, such as oil rigs and bridge structures. Since it is capable of travelling on water as well as submerged, the vessel can quickly travel to the right location on the surface before submerging down to the desired depth.

The vessel consists of outer and inner tubes, plus an underneath compartment that holds the main fuel tank and lightweight batteries. The underneath compartment can be flooded to aid submerging and keep the vessel stable underwater. The outer tubes will normally be open, but can be closed if necessary. The inner tubes are inflatable and will be used to provide positive buoyancy when its time to resurface.

Chihuahua survives 24 hours inside sunken riverboat

Fancy, a four-year-old Chihuahua, survived for more than 24 hours under water after being left inside a capsized riverboat. She was onboard a houseboat that sunk in the river near Toledo, USA after hitting a stump.

As the 44 foot houseboat went under, none of the four passengers remembered to take the Chihuahua with them to dry land. When she was missed, they thought it was too late to save her and didn’t return to the wreck until 24 hours.

But Fancy wasn’t dead, she was stuck in an air-pocket with her body – but not her head – submerged under water.

“Over to my right side I heard her little feet go too,too, too, too. I was almost like a whale going offthe side of the boat,” said Rebel Barrett, the owner of the dog. “I just got in the water and I grabbed her and I was crying, and screaming, and hugging her and kissing her and shewas happy to see her mama.”

The owner of the houseboat, who happened to be a scuba diver, went down and rescued Fancy from the air wreck.

“I just turned my head slightly, and I looked in and I saw her sitting there with her head on her paws, just shaking and quivering,” said the astounded boat owner. “The air pocket was maybe two or three inches, just a little bitty pocket, but she was sittin up there in it. It’s a miracle.”

Scientists hope to develop ballast water treatment

Ballast water is great for stabilizing a ship in rough waters. Unfortunately, it is equally great at carrying all sorts of aquatic organisms across the world before releasing them into new ecosystems where many of them become problematic invasive species.

The cost of invasive species in the Great Lakes of North America have now reached $200 million a year and scientists predict that this number will increase sharply if the dreaded fish virus known as VHS manage to hitchhike its way into Lake Superior. Considering the number of international shipping vessels that arrive to this river system each week, it is probably just a matter of time unless drastic measures are put in place to stop the costly carrying of disruptive stowaways.

Is ballast treatment the solution?

On-board ballast treatment systems have been proposed by parts of the shipping industry as well as by many scientists, but so far, no one has been able come up with an efficient, cost-effective and safe solution that will work in both freshwater and saltwater. Researchers from the Lake Superior Research Institute* in Superior are now trying to change this.

“The question is how clean is clean? Zero would be great, but is it achievable?” asks Mary Balcer, director of the Lake Superior Research Institute.

Balcer, her research team and students at the University of Wisconsin-Superior are currently analyzing a long row of different solutions developed by private companies to see if any of them could help protect environments such as the Great Lakes from the threat of marauding newcomers.

The goal is to find a solution that will eliminate as many living organisms as possible before the ballast water is released. The treatment must also be safe for the ecosystem into which the water will be released.

Freshwater more demanding

Last month, researcher Tom Markee and several students tested using chlorine to eliminate organisms such as tiny worms, midges and water fleas growing in fish tanks in the university lab. Carrying large containers of chlorine on a ship is naturally dangerous, so Markee and his team instead opted for a solution where the treatment system produces its own chlorine by exposing saltwater to an electric current. The goal for Markee et al is now to find the ideal dose of chlorine as well as make sure that the system works in different types of water.

“They’ve tested it in saltwater and it works fine, but when you get to harbors or a river system, that’s when it becomes less effective,” Markee explains.

Other examples of techniques that are being explored by the research institute are the use of ultraviolet light, ozone and even lethal inaudible sound.

Balcer says her research team hasn’t yet found any viable treatment system that would kill all the living organisms in a ballast tank, but she’s happy with the progress that’s been made.

“Everyone’s behind getting the problem solved,” she says. Eventually we’ll be able to find something that really works.”

* Lake Superior Research Institute, http://www.uwsuper.edu/wb/catalog/general/2006-08/programs/LSRI.htm

Florida fisherman spends 10 days next to live missile; ” it was kind of a fright”

When long-line fishing boat captain Rodney Solomon reeled in an air-to-air missile 50 miles (80km) off Panama City in Florida, he did what anyone would have done – strapped it to his boat and enjoyed the remaining 10 days of his fishing trip.

After returning from his trip, Solomon reported his unusual find to the local fire department only to find out that the missile was live and could have gone off any time.

Mr Solomon told local news organisation WTSP that fishermen are used to being in danger and are usually unflappable. “We’re fishermen, nothing scares us!”

But he admits that this experience “was kind of a fright“.

“It was like, ‘wow man, you all took a big chance bringing in this missile, he said. “You had it on your boat for 10 days and any time it could have exploded on you.”

Sidewinder

Solomon had assumed that the missile had gone off earlier since he found a hole in it.

“He actually came to the fire station and told us he had caught a Tomahawk missile, said local fire chief, Derryl O’Neal, “but it turned out not to be – it was an air-to-air guided missile, known as a Sidewinder“.

The firemen quickly evacuated the area around the missile until and the deadly device could eventually be dismantled without causing any damages. The missile was caught in or near a zone used by defence forces for testing.

Local fishermen are being advised not to bring in any similar discovery, but to alert authorities to its exact location.

U.S. citizen heavily fined for injuring Belize reef

Two years after destroying part of the Belize barrier reef, an U.S. skipper has been ordered by a Belize court to pay BZ$3.4 million, roughly equivalent of US$1.7 million, for the damage.

On May 2, 2007, the skipper was trying to reach harbour in his double hull catamaran when it ran aground in the Lighthouse Reef Atoll, causing damage to a piece of the reef measuring 125 feet by 75 feet.

Belizean magistrate Ed Usher ruled that the skipper did not exercise due diligence in navigating the atoll. Since the catamaran was so large, 37 feet x 21 feet, the person in charge should have hired a pilot and sufficient crew to navigate the reef safely. By neglecting to do so, the skipper recklessly caused a disaster that resulted in a loss to the environment.

The skipper must pay BZ$50,000 (US$25,000) within two months, but have been given a five year respite for the remainder of the fine. His catamaran, estimated to be worth around US$300,000, will however be held by Belizean authorities until he comes up with the money.

Craggy hull resists barnacles; makes toxins superfluous and may save ship owners millions

North Carolina State University engineers have created a non-toxic ship hull coating that resists the build up of barnacles.

Barnacles that colonize the hull of a ship augment the vessel’s drag which in turn increases fuel consumption. After no more than six months in salt water, the fuel consumption of a ship has normally swelled substantially, forcing the ship owner to either spend more money on fuel or to remove the ship from the water and place it in a dry dock where it can be cleaned. Both alternatives are naturally costly, and for many years ship owners fought barnacles by regularly coating ship hulls with substances toxic to barnacles. Unsurprisingly, these substances turned out to be toxic to a wide range of other marine life as well, including fish, which caused most countries to ban their use.

Ships are not the only ones colonized by barnacles. In the wild, it is common to see barnacles attached to a wide range of marine species, such as whales and sea turtles. One type of animal is however usually free of barnacles: the sharks. Unlike the smooth-skinned whales, sharks tend to have rough and uneven skin, and this might prove to be the salutation for ships as well.

The new hull coating created by Dr. Kirill Efimenko, research assistant professor in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, and Dr. Jan Genzer, professor in the same department, contains nests of different-sized “wrinkles” which makes the surface rough and uneven, just like the skin of a shark.

The wrinkly material was tested in Wilmington, N.C and remained free of barnacles after 18 months of exposure to seawater. Flat coatings made of the same material were on the other hand colonized by barnacles within a month.

“The results are very promising,” says Efimenko. “We

are dealing with a very complex phenomenon. Living

organisms are very adaptable to the environment, so

we need to find their weakness. And this hierarchical

wrinkled topography seems to do the trick.”

Efimenko and Genzer created the wrinkles by stretching a rubber sheet, exposing it to ultra-violet ozone, and then relieving the tension, causing five generations of “wrinkles” to form concurrently. After that, the coating was covered in an ultra-thin layer of semifluorinated material.

Vandenberg sunk in 1 minute and 54 seconds

As reported earlier here and here, the retired 523-foot military vessel “Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenberg” was scheduled to be sunk this month to become an artificial reef off the Floridian coast, and we can now happily report that everything has gone according to plan.

After being slightly delayed last minute by a sea turtle venturing into the sinking zone, Vandenberg was successfully put to rest roughly 7 miles south-southeast of Key West at 10:24 a.m., May 27.

Once 44 carefully positioned explosive charges had been detonated, Vandenberg gracefully slipped below the water’s surface in no more than 1 minute and 54 seconds. It is now resting rightside-up on the sea bottom at a depth of roughly 140 feet (43 metres) in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

Divers and other underwater specialists are currently surveying the ship to make sure it is safe for the public to explore. Hopefully, Vandenberg will open up for public diving by Friday morning.

Over 20 cameras were mounted on the vessel to capture images of it descending into the blue, cameras that are now being retrieved by an underwater team.

Vandenberg is the second largest vessel ever intentionally sunk to become an artificial reef. In 2006, the 888-foot long USS Oriskany, also known as CV-34, was sunk in the Gulf of Mexico, south of Pensacola, Florida.

Shark-Free Marinas

Brooks is a scientific advisor for the not-for-profit Company Shark-Free Marina Initiative, SFMI, who has just instigated a new strategy for preventing the deaths of millions of sharks belonging to vulnerable or endangered species.

The Shark-Free Marina Initiative works by prohibiting the landing of any caught shark at a participating marina. The initiative is based on the Atlantic billfish model which banned the mortal take of billfish in the 1980’s to give severely depleted populations a chance to recover.

By promoting catch-and-release and working closely with marinas and game fishing societies, SFMI hopes to win over the fishing community. Other important allies in the endeavour are competition sponsors and tackle producers.

Collaborating with the Fisheries Conservation Foundation in the USA and the Cape Eleuthera Institute in the Bahamas, SFMI has already gained the attention of marinas and non-profits nation-wide.

Enlisting the aid of anglers

By practising catch-and-release, sport fishers can not only decrease their impact on shark species; they can also actively aid ongoing research studies by collecting valuable data.

“Although the number of sharks killed by recreational fishermen each year is dwarfed by commercial catches, the current crisis facing shark stocks requires action wherever possible.” says Brooks.

During the last five years, the average number of sharks harvested annually by sport- and recreational anglers in the United States exceeded half a million. The outlook for these shark populations seem even graver when you take into account that many of the sharks targeted by fishermen are large, breeding age specimens belonging to endangered or vulnerable species. Removing so many sexually mature specimens from a population each year naturally has a major impact on its chances of long-term survival.

“Shark-Free Marinas is a necessary response to the culture of mature shark harvest” says SFMI’s Board Director, Marine Biologist Luke Tipple “Our effect will be immediate, measurable and, together with saving millions of sharks, will establish a new global standard for responsible ocean management. There’s a lot of talk about the atrocity of shark fining and fishing worldwide, but not a lot of measurable action towards reversing the damage. The time has come to stop simply ‘raising awareness’ and start implementing sensible management techniques to protect vulnerable species of sharks from inevitable destruction.”

You can find more information at www.sharkfreemarinas.com.

Help the project!

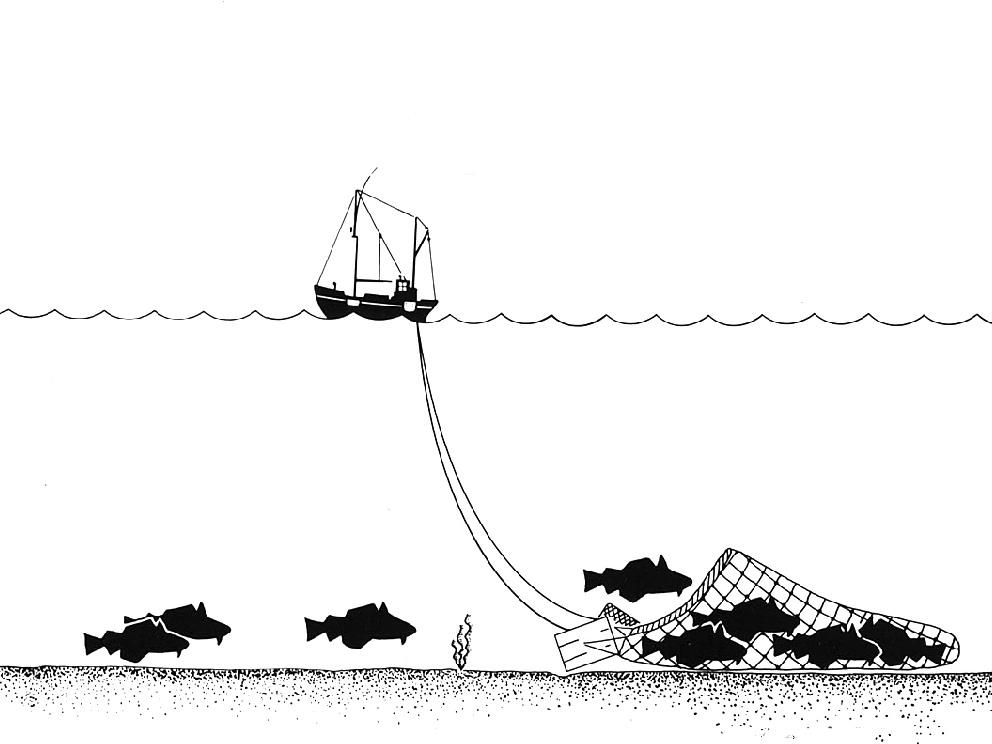

Are trawlers obliterating historic wrecks?

An example of the damage trawlers can cause is the wreck of HMS Victory, a British warship sunk in the English Channel in 1744. Trawling nets and cables have become entangled around cannon and ballast blocks, and three of the ship’s bronze cannons have been displaced. One of them, a 42-pound (19 kg) cannon weighing 4 tonnes, has been dragged 55 metres (180 feet) and flipped upside down. Two other cannon recovered by Odyssey Marine Exploration last year show fresh scratches from trawls and damage caused by friction from nets or cables.

“We know trawlers work the Victory site because one almost ran us down while we were there,” says Tom Dettweiler, senior project manager of Odyssey Marine Exploration.

“It turns out that Victory is right in the middle of the heaviest trawling area in the Western Channel,” says Greg Stemm, chief executive of the company. “We were shocked and surprised by the degree of damage we found in the Channel, he continues. “When we got into this business, like everyone else we thought that beyond 50 or 60 metres, below the reach of divers, we’d find pristine shipwrecks. We thought we’d be finding rainforest, but instead found an industrial site criss-crossed by bulldozers and trucks.”

While surveying 4,725 sq miles (12,300 sq km) of the western Channel, Odyssey Marine Exploration found 267 wrecks, of which 112 showed evidence of being damaged by bottom trawlers. That is over 40 percent.

The English Channel has been a busy area for at least three and half millennia and was thought to be littered with wrecks. In these fairly cold waters, wooden ships tend to stay intact for much longer periods of time than they would in warm tropical regions. Strangely enough, Odyssey Marine Exploration found no more than three pre-1800 wrecks when surveying the area using modern technology sensitive enough to disclose a single amphora. According to historic estimations, at least 1,500 ships have been lost in these waters so finding no more than three pre-1800 wrecks calls for further investigation.

Odyssey Marine Exploration blames bottom trawlers for the lack of wrecks. “The conclusion and fear is that the vast majority of pre-1800 sites have already been completely obliterated by the deep-sea fishing industry,” says Sean Kingsley, of Wreck Watch International, the author of the Odyssey report.

Odyssey Marine Exploration is the world’s only publicly-listed shipwreck exploration company and critics argue that these American treasure hunters are overstating the damage for their own gain.

“You have to ask why Odyssey is doing such a study,” said Robert Yorke, chairman of the Joint Nautical Archaeology Policy Committee. “They want to pressurise the UK Government to allow them to get at the wreck . . . the Victory hasn’t disappeared since 1744; it’s not going to disappear tomorrow.”

The Ministry of Defence has jurisdiction over warships’ remains and it has asked English Heritage for an assessment of the threats to the site. English Heritage has a policy of leaving shipwrecks untouched on the seabed unless a definite risk can be shown.

100 pyramids sunk off Alabama to promote marine life

Alabama fishermen and scuba divers will receive a welcome present from the state of Alabama in a few years: the coordinates to a series of man-made coral reefs teaming with fish and other reef creatures.

In order to promote coral growth, the state has placed 100 federally funded concrete pyramids at depths ranging from 150 to 250 feet (45 to 75 metres). Each pyramid is 9 feet (3 metres) tall and weighs about 7,500 lbs (3,400 kg).

The pyramids have now been resting off the coast of Alabama for three years and will continue to be studied by scientists and regulators for a few years more before their exact location is made public.

In order to find out differences when it comes to fish-attracting power, some pyramids have been placed alone while others stand in groups of up to six pyramids. Some reefs have also been fitted with so called FADs – Fish Attracting Devices. These FADs are essentially chains rising up from the reef to buoys suspended underwater. Scientists hope to determine if the use of FADs has any effect on the number of snapper and grouper; both highly priced food fishes that are becoming increasingly rare along the Atlantic coast of the Americas.

Early settlers and late followers

Some species of fish arrived to check out the pyramids in no time, such as grunt and spadefish. Other species, like sculpins and blennies, didn’t like the habitat until corals and barnacles began to spread over the concrete.

“The red snapper and the red porgies are the two initial species that you see,” says Bob Shipp, head of marine sciences at the University of South Alabama. After that, you see vermilion snapper and triggerfish as the next order of abundance. Groupers are the last fish to set in.”

Both the University of South Alabama and the Alabama state Marine Resources division are using tiny unmanned submarines fitted with underwater video cameras to keep an eye on the reefs and their videos show dense congregations of spadefish, porgies, snapper, soap fish, queen angelfish and grouper.

“My gut feeling is that fish populations on the reefs are a reflection of relative local abundance in the adjacent habitat,” says Shipp. “Red snapper and red porgy are the most abundant fish in that depth. They forage away from their home reefs and find new areas. That’s why they are first and the most abundant.”

What if anyone finds out?

So, how can you keep one hundred 7,500 pound concrete structures a secret for years and years in the extremely busy Mexican Gulf? Shipp says he believes at least one of the reefs has been discovered, since they got only a few fish when they sampled that reef using rod and reel. Compared to other nearby pyramid reefs, that yield was miniscule which may indicate that fishermen are on to the secret. As Shipp and his crew approached the reef, a commercial fishing boat could be seen motoring away from the spot.