Category Archives: Fishing

Discarding fish at sea may be banned, EU officials say

“What’s the point of setting a quota if fishermen aren’t accountable for the fish they actually catch?” says Mogens Schou, a Danish fishery official.

The EU’s quotas limit the size of the annual catch that countries and their fleets can sell on their return to harbour, but instead of protecting remaining fishing populations from depletion, the system is making fishermen dump lower-value fish at sea to maximize profit. According to officials in the European Commission’s fisheries office, most of these fishes do not survive.

“To stay under their quotas, and make more money, fishermen discard half of what they catch,” says Schou, “They ‘high-grade’ – in other words, only keep the most profitable fish.”

Last month, an EU report was released highlighting the failure of current EU fishing regulations by showing that 88% of fish species in EU waters are being fished out faster than they can reproduce. In response to the report, fishery ministers from the 27 EU nations are currently discussing how to protect the remaining fish stocks from complete eradication.

As a part of these talks, Denmark has proposed an amended quota system where fishermen and their countries are held accountable for the amount of fish caught rather than the amount returned to port. To make it harder for fishing fleets to cheat, Denmark is also proposing that fishermen voluntarily equip their boats with on-board cameras. In exchange, the fishermen would get bigger quotas.

Denmark has already designed a surveillance kit consisting of four cameras, a GPS (Global Positioning System) device, and sensors that notice when fish is being hauled or dumped. The Danish kits are currently being used on six fishing boats with Danish officials monitoring the footage.

Danish fisherman Per Nielsen installed the kit on his trawler Kingfisher in September and believes it to be a good investment. The kit cost roughly 10,000 USD, but Nielsen was compensated by being allowed to catch several extra tens of thousands of dollars worth of cod.

As of now, EU fishermen throw overboard an estimated 50% of the fish they catch and did for instance dump 38% of the 24,000 tons of cod they caught last year, according to the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea.

History of Trawling; not a modern problem

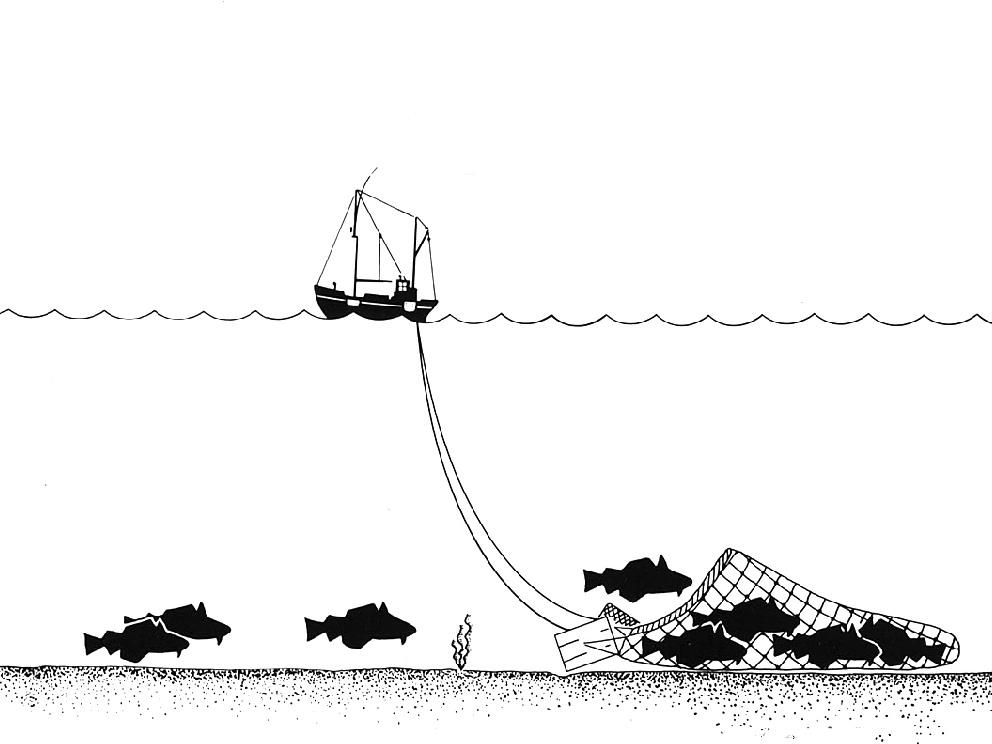

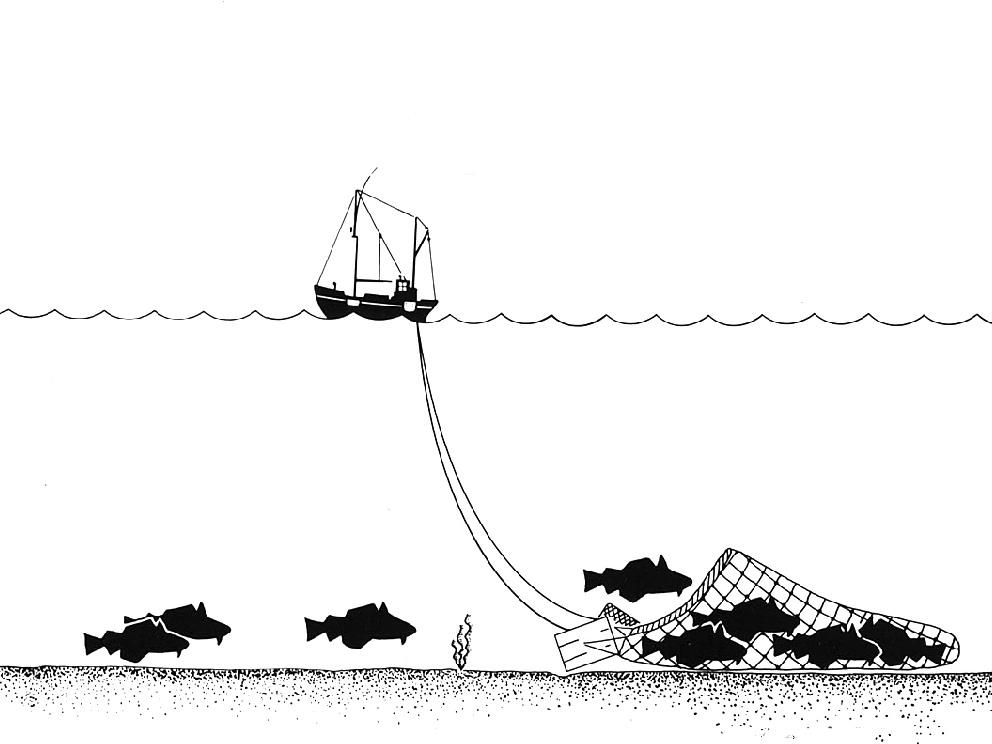

One of the earliest known complaints regarding trawling is in fact 400 years older than the U.S. Declaration of Independence and over two centuries older than all the Shakespeare plays; it dates back to the European Middle Ages but raises the same questions as we discuss to today: the effect of trawling on the ecosystem, the consequences of a small mesh size, and industrial fishing for animal feed.

During the reign of Edward III, a petition was presented to the British Parliament in 1376 calling for the prohibition of a “subtlety contrived instrument called the wondyrchoum”. According to the petition, the wondyrchoum was a type of beam trawl, which caused extensive damage to the environment in which it was used.

“Where in creeks and havens of the sea there used to be

plenteous fishing, to the profit of the Kingdom, certain fishermen

for several years past have subtily contrived an instrument

called ‘wondyrechaun’ […] the great and long iron of the

wondyrechaun runs so heavily and hardly over the ground when

fishing that it destroys the flowers of the land below water there,

and also the spat of oysters, mussels and other fish up on which

the great fish are accustomed to be fed and nourished. By which

instrument in many places, the fishermen take such quantity of

small fish that they do not know what to do with them; and that

they feed and fat their pigs with them, to the great damage of the

common of the realm and the destruction of the fisheries, and

they prey for a remedy.”

According to the letter, a wondyrchoum had a 6 m (18 ft) long and 3 m (10 ft) wide net

“[…] of so small a mesh, no manner of fish, however small, entering within it can pass out and is compelled to remain therein and be taken […].”

Another source* describes the wondyrchoun as ” […] three fathom long and ten mens’ feet wide, and that it had a beam ten feet long, at the end of which were two frames formed like a colerake, that a leaded rope weighted with a great many stones was fixed on the lower part of the net between the two frames, and that another rope was fixed with nails on the upper part of the beam, so that the fish entering the space between the beam and the lower net were caught. The net had maskes of the length and breadth of two men’s thumbs.”

The Crown responded to the 14th century complaint by letting “[…] Commission be made by qualified persons to inquire and certify on the truth of this allegation, and thereon let right be done in the Court of Chancery”.

Eventually, bans were introduced regulating the use of wondyrchoums in the kingdom and in 1583 two fishermen were actually executed for using metal chains on their beam trawls.

British fishermen continued to use trawl nets despite the ban, but trawling didn’t become the ravishingly successful fishing method of today until the advent of steam power and diesel engines in the 19th and 20th century.

In 1863, a Royal Commission was established in Great Britain to investigate the accusations against trawling, among other complaints. One of the arguments presented by the defence was a witness who, when asked what food fish eat, replied:

“There is when the ground is stirred up by the trawl. We think the

trawl acts in the same way as a plough on the land. It is just like

the farmers tilling their ground. The more we turn it over the

great supply of food there is, and the greater quantity of fish we

catch.”**

The Royal Commission also noted that when a trawler harvests an area already harvested by another trawler, the second trawler usually catches even more fish than the first. This was interpreted as a sign of the benevolence of trawlers, when in fact the high second yield is caused by how the destruction inflicted on the area by the first trawler results in an abundance of dead and dying organisms which, temporarily, attracts scavenging fish.

The result of the Royal Commission’s investigations was the abandonment of over 50 Acts of Parliament and a switch to virtually unrestricted sea fishing. Today, the 14th century issue of destructive fishing practises is more acute than ever.

* Davis, F (1958), An account of the fishing gear of England and Wales, 4th Edition, HMSO

** Roberts, C (2007), The Unnatural History of the Sea, Gaia

Are fish getting increasingly suspicious of hooks?

The inclination to end up stuck on a hook seems to be a heritable trait in bass, according to a study published in a recent issue of the Transactions of the American Fisheries Society.

The study, which was carried out by researchers DP Philipp, SJ Cooke, JE Claussen, JB Koppelman, CD Suski, and DP Burkett, focused on Ridge Lake, an Illinois lake where catch-and-release fishing has been enforced and strictly regulated for decades. Each caught fish has been measured, tagged and then released back into the wild.

Picture by: Clinton & Charles Robertson from Del Rio, Texas & San Marcos, TX, USA

David Philipp and coauthors commenced their study in 1977, checking the prevalence of Largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) on the hooks of fishermen. After four years, the experimental lake was drained and 1,785 fish were collected. When checking the tags, Philipp and his team found that roughly 15 percent of the Largemouth bass population consisted of specimens that had never been caught. They also found out that certain other bass specimens had been caught over and over again.

To take the study one step further, the research team collected never caught bass specimens (so called Low Vulnerability, LV, specimens) and raised a line of LV offspring in separate brood ponds. Likewise, the team collected bass specimens caught at least four times (High Vulnerability, HV, specimens) and placed them in their own brooding ponds to create a HV line.

The first generation (F1) offspring from both lines where then marked and placed together in the same pond. During the summer season, anglers where allowed to visit the pond and practise catch-and-release, and records where kept of the number of times each fish was caught.

As the summer came to an end, HV fish caught three or more times where used to create a new line of HV offspring, while LV fish caught no more than once became the parents of a new LV line.

The second generation (F2) offspring went through the same procedure as their parents; they were market, released into the same pond, and subjected to anglers throughout the summer. In fall, scientists gathered the fish that had been caught at least three times or no more than once and placed them in separate ponds to create a third generation (F3) HV and LV fish.

A following series of controlled fishing experiments eventually showed that the vulnerability to angling of the HV line was greater than that of the LV line, and that the differences observed between the two lines increased across later generations.

If this is true not only for bass but for other fish species as well, heavy hook-and-line angling pressure in lakes and rivers may cause evolutionary changes in the fish populations found in such lakes. Hence, a lake visited by a lot of anglers each year may eventually develop fish populations highly suspicious of the fishermen’s lure.

More information can be found in the paper published in Transactions of the American Fisheries Society: Philipp, DP, SJ Cooke, JE Claussen, JB Koppelman, CD Suski and

DP Burkett (2009) Selection for vulnerability to angling in Largemouth Bass. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 138, pp. 189–199.

Are trawlers obliterating historic wrecks?

An example of the damage trawlers can cause is the wreck of HMS Victory, a British warship sunk in the English Channel in 1744. Trawling nets and cables have become entangled around cannon and ballast blocks, and three of the ship’s bronze cannons have been displaced. One of them, a 42-pound (19 kg) cannon weighing 4 tonnes, has been dragged 55 metres (180 feet) and flipped upside down. Two other cannon recovered by Odyssey Marine Exploration last year show fresh scratches from trawls and damage caused by friction from nets or cables.

“We know trawlers work the Victory site because one almost ran us down while we were there,” says Tom Dettweiler, senior project manager of Odyssey Marine Exploration.

“It turns out that Victory is right in the middle of the heaviest trawling area in the Western Channel,” says Greg Stemm, chief executive of the company. “We were shocked and surprised by the degree of damage we found in the Channel, he continues. “When we got into this business, like everyone else we thought that beyond 50 or 60 metres, below the reach of divers, we’d find pristine shipwrecks. We thought we’d be finding rainforest, but instead found an industrial site criss-crossed by bulldozers and trucks.”

While surveying 4,725 sq miles (12,300 sq km) of the western Channel, Odyssey Marine Exploration found 267 wrecks, of which 112 showed evidence of being damaged by bottom trawlers. That is over 40 percent.

The English Channel has been a busy area for at least three and half millennia and was thought to be littered with wrecks. In these fairly cold waters, wooden ships tend to stay intact for much longer periods of time than they would in warm tropical regions. Strangely enough, Odyssey Marine Exploration found no more than three pre-1800 wrecks when surveying the area using modern technology sensitive enough to disclose a single amphora. According to historic estimations, at least 1,500 ships have been lost in these waters so finding no more than three pre-1800 wrecks calls for further investigation.

Odyssey Marine Exploration blames bottom trawlers for the lack of wrecks. “The conclusion and fear is that the vast majority of pre-1800 sites have already been completely obliterated by the deep-sea fishing industry,” says Sean Kingsley, of Wreck Watch International, the author of the Odyssey report.

Odyssey Marine Exploration is the world’s only publicly-listed shipwreck exploration company and critics argue that these American treasure hunters are overstating the damage for their own gain.

“You have to ask why Odyssey is doing such a study,” said Robert Yorke, chairman of the Joint Nautical Archaeology Policy Committee. “They want to pressurise the UK Government to allow them to get at the wreck . . . the Victory hasn’t disappeared since 1744; it’s not going to disappear tomorrow.”

The Ministry of Defence has jurisdiction over warships’ remains and it has asked English Heritage for an assessment of the threats to the site. English Heritage has a policy of leaving shipwrecks untouched on the seabed unless a definite risk can be shown.

World’s first Bigeye tuna farm may be placed off the coast of Hawaii

A Hawaiian company wants to build the world’s first commercial Bigeye tuna farm, in hope of creating a sustainable alternative to wild-caught big eye.

Bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus, is the second most coveted tuna after the famous Bluefin tuna and the wild populations have been seriously depleted by commercial fishing fleets. As Bluefin is becoming increasingly rare due to over-fishing, consumers are turning their eyes towards Thunnus obesus – which naturally puts even more stress on this species that before.

In 2007, fishermen caught nearly 225,000 tons of wild Bigeye in the Pacific. Juvenile bigeye tuna like to stay close to floating objects in the ocean, such as logs and buoys, which make them highly susceptible to purse seine fishing in conjunction with man-made FADs (Fish Aggregation Devices). The removal of juvenile specimens from the sea before they have a chance to reach sexual maturity and reproduce is seriously threatening the survival of this tuna species.

“All indications are we’re on a rapid race to deplete the ocean of our food resources,” said Bill Spencer, chief executive of Hawaii Oceanic Technology Inc. “It’s sort of obvious _ well, jeez we’ve got to do something about this.”

Techniques to spawn and raise tuna fry are still being tentatively explored by scientists in several different countries, including Australia and Japan. As of today, most tuna farms rely on fishermen catching juvenile fish for them, but Hawaii Oceanic Technology plans to artificially hatch Bigeye tuna at a University of Hawaii lab in Hilo.

Once the young tunas from the lab have grown large enough, they will be placed in the 12-pen tuna farm that Hawaii Oceanic is planning to build roughly 3 miles off Big Island’s west coast. Each pen will have a diameter of 50 metres (168 feet) and the entire farm will be spread out over one square kilometre (250 acres). If everything goes according to plan, this project will yield 6,000 tons of Bigeye per annum. The fish will not be harvested until it reaches a weight of at least 45 kg (100 lbs).

In an effort to avoid many of the common problems associated with large scale commerical fish farmning, Hawaii Oceanic Technology will place their pens at a depth of 1,300 feet (400 metres) where currents are strong. The company also plans to keep their pens lightly stocked, since dense living conditions are known to increase the risk of disease in fish farms.

Farming pens can cause problems for the environment if fish waste and left-over food is allowed to collect under the pens, suffocating marine life living beneath. Other problems associated with fish farming are the release of antibiotics into the water and the escape of invasive species.

Fish farms can also put pressure on fish further down in the food chain since vast amounts of food is necessary to feed densely packed fish pens, and Peter Bridson, aquaculture manager at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California, is concerned about how much fish meal the Hawaiian farm will use need to feed its tuna.

“You kind of have to come back to the whole debate on whether these fish are the right thing for us humans to be eating,” said Bridson. “There are lots of other things which have a lower impact in terms of how they are farmed.”

Spencer shares this concern and says Hawaii Oceanic wish to eventually develop other ways of feeding their fish, e.g. by creating food from soybeans or algae. It might also be possible to decrease the need for fish meal by recycling fish oil from the farm itself.

“We’re concerned about the environmental impact of what we’re doing,” Spencer said. “Our whole goal is to do this in an environmentally responsible manner.”

Will captive bred tuna save depleted wild populations?

An important step in the ground-breaking Clean Seas Tuna breeding program was taken today when millions of dollars worth of Southern Bluefin Tuna was airlifted from sea pens off South Australia’s Eyre Peninsula to an on-shore breeding facility at Arno Bay.

The Southern Bluefin Tuna is a highly appreciated food fish and the remaining wild populations are continuously being ravished by commercial fishing fleets, despite the species status as “critically endangered” on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

The Australian tuna breeding program is the first of its kind and will hopefully help ease the strain on wild populations. The air transfer was made to provide the breeding program with an egg supply ahead of the spawning period.

As reported earlier, the Australian company Clean Seas Tuna managed to successfully produce Southern Bluefin Tuna fingerlings in March this year and they are now hoping to commence commercial production of the species no later than October.

WWF Australia’s fisheries program manager Peter Trott says any advancement that would reduce pressure on wild tuna stocks is welcome, but he also cautions against the environmental problems associated with large-scale aquacultures. It is for instance common to use other fish to feed farmed fish, which can put pressure on wild fish populations.

European Commission: Scientists in the dark on state of European fish stocks

Scientists are unaware of the state of nearly two-thirds of Europe’s fish stocks and do not have enough information to assess the exact scale of the crisis the European fishing industry is facing, says the European Commission.

This is naturally alarming, since the commission last month admitted that nothing short of a completely new fisheries management system based on scientific evidence could stop the downward spiral of years of dangerously depleted fish stocks and get the struggling European fishing industry back on its feet.

Europe

The European Commission is now proposing smaller annual EU fish catch quotas and have given governments and industry representatives until the end of July to submit their views.

“The contribution of EU fisheries to the European economy and food supply is far smaller today than it was in the past. Even more worryingly, the status of some 59 per cent of stocks is unknown to scientists, largely due to inaccurate catch reporting,” the European Commission says in an official statement.

The policy has not been reformed since 2002 and the European Commission admits there has been “slow progress” in stock recovery, since quotas consistently have been set at unsustainably high levels.

Turkish government sawing of the branch their own fishermen are sitting on

The Turkish government has set their own very high catch limit for endangered Mediterranean bluefin tuna without showing any regard for internationally agreed quotas and the survival of this already severally overfished species. By telling the Turkish fishermen to conduct this type of overfishing, the Turkish government is effectively killing the future of this important domestic industry.

Turkey currently operates the largest Mediterranean fleet fishing for bluefin tuna, a commercially important species that – if properly managed – could continue to create jobs and support fishermen in the region for years and years to come. Mediterranean societies have a long tradition of fishing and eating bluefin tuna and this species was for instance an appreciated food fish in ancient Rome. Today, rampant overfishing is threatening to make the Mediterranean bluefin tuna a thing of the past.

Management of bluefin tuna is entrusted to the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), an intergovernmental organisation. Last year, the Turkish government objected to the Bluefin tuna quota that was agreed upon at the ICCAT meeting in November and is now ignoring it completely.

The agreed tuna quota is accompanied by a minimum legal landing size set at 30 kg to make it possible for the fish to go through at least one reproductive cycle before it is removed from the sea, but this important limit is being widely neglected as well. Catches below the 30 kg mark have recently been reported by both Turkish and Italian media.

To make things even worse, Mediterranean fishermen are also involved in substantial illegal catching and selling of Mediterranean bluefin tuna. This year’s tuna fishing season has just begun and Turkish fishermen have already got caught red-handed while landing over five tonnes of juvenile bluefin tuna in Karaburun.

According to scientific estimations, Mediterranean blue fin tuna fishing must be kept at 15,000 tonnes a year and the spawning grounds must be protected during May and June if this species shall have any chance of avoiding extinction in the Mediterranean. This contrasts sharply against the actual hauls of 61,100 tonnes in 2007, a number which is over four times the recommended level and twice the internationally agreed quota. The crucial spawning grounds are also being ravished by industrial fishing fleets.

By blatantly ignoring international quota limits, the Turkish government is in fact threatening not only the tuna but also the future livelihood of numerous Mediterranean fishermen, including the Turkish ones.

100 pyramids sunk off Alabama to promote marine life

Alabama fishermen and scuba divers will receive a welcome present from the state of Alabama in a few years: the coordinates to a series of man-made coral reefs teaming with fish and other reef creatures.

In order to promote coral growth, the state has placed 100 federally funded concrete pyramids at depths ranging from 150 to 250 feet (45 to 75 metres). Each pyramid is 9 feet (3 metres) tall and weighs about 7,500 lbs (3,400 kg).

The pyramids have now been resting off the coast of Alabama for three years and will continue to be studied by scientists and regulators for a few years more before their exact location is made public.

In order to find out differences when it comes to fish-attracting power, some pyramids have been placed alone while others stand in groups of up to six pyramids. Some reefs have also been fitted with so called FADs – Fish Attracting Devices. These FADs are essentially chains rising up from the reef to buoys suspended underwater. Scientists hope to determine if the use of FADs has any effect on the number of snapper and grouper; both highly priced food fishes that are becoming increasingly rare along the Atlantic coast of the Americas.

Early settlers and late followers

Some species of fish arrived to check out the pyramids in no time, such as grunt and spadefish. Other species, like sculpins and blennies, didn’t like the habitat until corals and barnacles began to spread over the concrete.

“The red snapper and the red porgies are the two initial species that you see,” says Bob Shipp, head of marine sciences at the University of South Alabama. After that, you see vermilion snapper and triggerfish as the next order of abundance. Groupers are the last fish to set in.”

Both the University of South Alabama and the Alabama state Marine Resources division are using tiny unmanned submarines fitted with underwater video cameras to keep an eye on the reefs and their videos show dense congregations of spadefish, porgies, snapper, soap fish, queen angelfish and grouper.

“My gut feeling is that fish populations on the reefs are a reflection of relative local abundance in the adjacent habitat,” says Shipp. “Red snapper and red porgy are the most abundant fish in that depth. They forage away from their home reefs and find new areas. That’s why they are first and the most abundant.”

What if anyone finds out?

So, how can you keep one hundred 7,500 pound concrete structures a secret for years and years in the extremely busy Mexican Gulf? Shipp says he believes at least one of the reefs has been discovered, since they got only a few fish when they sampled that reef using rod and reel. Compared to other nearby pyramid reefs, that yield was miniscule which may indicate that fishermen are on to the secret. As Shipp and his crew approached the reef, a commercial fishing boat could be seen motoring away from the spot.

Merchant ships top blame for littered sea

According to a new report jointly produced by UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and UN Environment Programme (Unep), merchant ships are to blame for 88 percent of the total marine littering in the world. According to the report, merchant ships deposit 5.6 million tonnes of litter in the ocean each year.

About 8 million pieces of marine litter enters our oceans each day and most of it is solid waste thrown overboard or accidently lost from ships. Right now, an average of 13,000 pieces of plastic litter is floating around per square kilometre of ocean waters, the report says.

The FAO-Unep report has been released right before next weeks’ World Oceans Conference in Manado, Indonesia where marine littering will be high on the agenda.

A majority of the litter from ships is fishing gear, which is either lost or intentionally abandoned in the water. Fishing gear now accounts for one tenth of all marine litter.

The rest consists of various debris, such as shipping containers, pallets, plastic covers, drums, wires and ropes. Accumulated oils are also dumped by ships; oils which can cause serious injury to marine life.

“Most fishing gear is not deliberately discarded but is lost in storms or strong currents or from’ gear conflicts’”, the report states. “For example, fishing with nets in areas where bottom-traps that can entangle them are already deployed.”

Unfortunately, lost and abandoned fishing gear will not stop fishing – they will continue to trap animals until they are broken down; a process which can take many years since modern fishing gear are made from highly durable synthetic materials. This is referred to as ghost fishing and is a major problem for aquatic species that need to surface regularly to breathe; a dolphin, turtle or seal caught in a net will suffocate and die. Lost fishing gears are also a problem for ships that become entangled in the equipment and are known to damage boats and cause accidents at sea.

While the report points a finger at merchant vessels, it also states that land-based sources are the main cause of marine littering in coastal regions.

UN recommends financial incentives and new technology

The report recommends using financial incentives to encourage fishers to bring old and damaged gear to port instead of dumping it. Fishers should also be given incentives to bring ghost nets recovered while fishing back to shore and to log and report items lost at sea. For this to work disposal facilities must be set up in ports and a report and recovery system must be established. The report also suggests providing ships with oversized, high-strength disposal bags to place discarded fishing gear in.

“A ‘no-blame’ approach should be followed with respect to liability for losses, their impacts, and any recovery efforts,” the report says.

New technologies – such as seabed imaging, geographic Positioning Systems (GPS), and transponders – can be used locate where lost or dumped fishing gear is present and recover it. Fishing ships could use GPS to mark locations where objects have been lost and weather monitoring technology could be used to predict there the stuff will go. It is also possible to attach transponders to fishing gear, shipping containers and other types or property known to frequently get lost at sea.

Weather monitoring technology can also reduce the risk of property getting lost at sea by altering captains in advance, e.g. to prevent them from deploying nets when unusually severe weather is on its way.

The study also recommends speeding up the development and commercial adoption of durable but bio-degradable fishing gear, including gear containing magnetic solutions.

International Convention

Ichiro Nomura, FAO assistant director general for fisheries and aquaculture, has called for industry and governments to take action to radically reduce the amount of lost and abandoned fishing gear in the sea. If nothing is done, fishing gear will continue to accumulate in the world’s oceans and their impact on marine ecosystems will become more and more severe. Nomura stressed that the problem must be addressed on multiple fronts and include both littering prevention and restoration measures.

FAO is currently involved in an ongoing review of Annex V of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) as regards fishing gear and shore side reception facilities by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO).