Tag Archives: scuba

Underwater Cavern Houses Extinct Bears

Scientists specializing in the area of underwater archeology, have just unearthed what appear to be four complete skulls of the extinct Arctotherium – a kind of stout faced bear which vanished off the face of the planet over 11,000 years ago – 42 meters beneath the waves, in an underwater cave on the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico.

The skulls, which measured between 25 and 30 centimeters, belonged to two adult bears – one male and one female – as well as two bears which had not yet reached adulthood. It is not known whether these bears were a family unit or not, and that answer is not likely going to be easy to find out from just the skulls of the bears. A team of scientists, led by Guillermo de Anda Alanis, from the Yucatan Autonomous University, unearthed these skulls when they were making a dive through the underwater caverns.

Along with the skulls of the bears, the team also uncovered the skeletons of five humans not too far away. As soon as the dating of the human skeletons has been completed, they will be able to ascertain if the two finds are related.

The discovery of the skulls will help to initiate a change of thinking when it comes to the biogeography of bears in the Americas – Arcotherium was believed to have only made its home in South America. The only living descendant of these prehistoric bears is the spectacled bear which makes its home in Venezuela.

Divers Haul Up Oldest Drinkable Beer From Baltic:

Well now, first it was champagne, now it’s beer.. The Baltic Sea seems to be a fully stocked bar in it’s own right. What’s next? A martini shaken not stirred?

Divers have managed to drag up an astounding find. This past Thursday they drudged up the world’s oldest drinkable beer from a shipwreck in the Baltic Sea this past Thursday, just in time for the weekend. This happens just days after efforts began to bring up cases of 200 year old champagne, officials in the area commented.

“We believe these are by far the world’s oldest bottles of beer,” a spokesman for the local government of Åland, Rainer Juslin, said in a statement.

The bottles of beer were discovered in a shipwreck which is though to be somewhere in the viciniy of 200 years old, as divers were just beginning to bring up bottles of champagne, discovered back in July. One question this reporter begs to ask… Is why the heck have they taken so long to start bringing up the bubbly?

The haul, which was found intact on the seabed somewhere around 50 meters down beneath the waves. The find comes from a wreck believed to have sunk off the coast sometime in the 18th century, officials of Aaland have postulated.

“The constant temperature and light levels have provided optimal conditions for storage, and the pressure in the bottles has prevented any seawater from seeping in through the corks,” a statement this Thurday said.

Malaysian researcher tries to save pygmy seahorse from reckless scuba divers

Scuba divers are threatening the survival of the infinitesimal Pygmy seahorses found on the coral reefs around Sabah’s east coast islands in Malaysia.

Sabah, a Malaysian state situated in the northern part of the island of Borneo, is home to two species of pygmy seahorse Hippocampus bargibanti and Hippocampus denise. Both species are fairly widespread in South East Asia and are found on coral slopes from southern Japan and Indonesia to northern Australia and New Caledonia.

Barely five years ago, the pygmy seahorses were discovered at popular Sabah divespots, such as Bodgaya, Mabul and Pulau Sipadan, and since then dive operators have brought large numbers of scuba divers to see the tiny creatures. In some of the most popular spots, over 100 divers can be seen exploring the reef simultaneously and this puts a lot of stress on the reef and its inhabitants.

Photographing divers have for instance been spotted breaking off sea fans – the natural habitat of the pygmy seahorses – and moved them just to get a better angle for their pictures.

In an effort to improve the conditions for the seahorses, marine biologist Yeong Yee Ling of the Universiti Malaysia Terengganu has held a two-day seminar about how to behave when scuba diving in seahorse habitat. The seminar was attended by 57 participants, including representatives from most of the 15 dive operators based in Semporna. Sabah Parks, the conservation-based statutory responsible for conserving the scenic, scientific and historic heritage of the state of Sabah, was also involved in the event.

“Our hope is that the discussions from the seminar would eventually be synthesised into a code of conduct for divers. We are thankful the dive operators have been supportive of this effort,” said Yeong, who has been researching pygmy seahorses for the past three years.

The seminar was funded by the Shell Malaysia’s Sustainable and Development Grant.

Maldives bans reef shark fishing by March 2010

The announcement was made by the Maldives Minister of State for Fisheries and Agriculture, Dr Hussein Rasheed Hassan, at the South West Indian Ocean Fisheries Commission steering committee meeting in Mombasa.

“We have realised that it is more economically viable to leave the shark and other sea creatures unharmed because the country currently earns about $7 million annually from the diving industry,” said the minister.

In 1998, the Maldives imposed a 10-year moratorium banning shark fishing around seven atolls that received a lot of vacationers from abroad. Now, the country intends to expand the ban to include all reef shark fishing across the Maldives within a 12 nautical mile radius (22km).

During recent years, the number of sharks in the Maldives has plummeted due to overfishing for the lucrative shark fin market.

“The marine ecosystem is very fragile and that is why we have to regulate activities that coupled with the treats of climate change could adversely affect the major sources of income for the country,” Hassan explained.

The Maldives is an island country consisting of a group of atolls stretching south of India’s Lakshadweep islands. Despite having a population of no more than roughly 300,000 individuals, the Maldives receives over 600,000 tourists each year.

‘Eat ‘um to beat ‘um – Lion hunt in the Bermudas

Bermuda‘s first Lionfish Tournament resulted in just four participants returning with lionfish for the weigh-in. Although this might sound disheartening, it is actually happy news for Lionfish project leader Chris Flook of the Bermuda Aquarium, Museum and Zoo since it indicates a relative scarcity of lionfish in Bermuda waters.

Lionfish is an invasive species in the Caribbean where it lacks naturally predators and multiplies uncontrollably. In the Bahamas, female lionfish spawn twice a month. Lionfish Tournaments like the one just held in the Bermudas is a way to boost public awareness and decimate the number of lionfish in the Caribbean. A Lionfish Tournament held in the Bahamas a few weeks ago resulted in the catch of about 1,400 lionfish.

“If we’d caught 1,000 fish it would have been very concerning, because it means it’s happening here like everywhere else,” Flook explained. “It means we may be ahead of the game and are potentially managing the population here in Bermuda.”

However, Flook also said that one of the reasons why not many fish were caught Bermuda’s Lionfish Tournament could be that they were hiding in deep waters following the storm surge of the recent Hurricane Bill and Tropical Storm Danny.

Mr. Flook began the Lionfish Culling Programme last year to encourage divers and fishermen to hunt down the species. Organised by environmental group Groundswell, the ‘Eat ‘um to beat ‘um’ event also aimed to show how invasive lionfish can be utilized as a food source.

“I think everybody who tasted it was very for it. It’s a great tasting fish,” said Flook, as Chris Malpas, executive chef at the Bank of Butterfield, cooked up samples of speared lionfish at Pier 41.

“The tournament has got the message out and so now hopefully people might start asking for lionfish in restaurants and fishermen will bring them in rather than throwing them overboard.

By eating lionfish we will take the pressure off some of our commercial fish. Every one you take is one less eating our juvenile fish,” said Flook.

If you want to know more about spearfishing lionfish in Bermudas, contact the Bermuda Aquarium at 293-2727 ext. 127, or the Marine Conservation Officer at 293-4464 extension 146 or e-mail lionfish@gov.bm. The Marine Conservation Officer should also be contacted if you see a lionfish in Bermuda waters.

Artificial reef to be created off the coast of Australia

An Australian frigate will be sunk off Terrigal on the New South Wales Central Coast to form an artificial reef.

Yesterday, the commonwealth handed over its decommissioned frigate HMAS Adelaide to the New South Wales government. HMAS Adelaide served the Royal Australian Navy for 27 years, participating in operations such as the Gulf War of 1991 and the East Timor peace-keeping mission of 1999. It has picked up capsized yachtsmen in the Southern Sea as well as rescued asylum seekers from a sinking ship.

“I think this is a great project, I’m very confident we’ll see HMAS Adelaide become a great national, and I suspect international, attraction for recreational divers […],” said Defence Minister John Faulkner.

NSW Premier Nathan Rees agrees with Faulkner.

“Coral will grow on the metal you see before you, fish will swim through the corridors that once rang with the sound of action stations,” he said. “And divers will find a place of contemplation and beauty as nature slowly reclaims her broken frame.”

The federal government will contribute up to 5.8 million AUS to make the ship is safe before it’s sunk.

Black Death destroying Green Island coral reefs

According to The China Post , no sewage treatment project has been prepared for the island since land can’t be procured for a sewage plant. Researchers now fear that the untreated sewage is to blame for the spread of the so called “Black Death” among the corals.

Chen Jhao-lun, a senior research fellow at the Academia Sinica who has studied the coral

reefs, describes the affected colonies as being covered slowly with a piece of black cloth.

“As this black sponge which multiplies itself covers the colonies, it shuts off sunlight to stop

photosynthesis by coral polyps,” Chen explains. The polyps die and no new corals are formed.

The “Black Death”, a type of necrosis, typically manifests in the form of black lesions that gradually spread across the surface of an infested colony.

However, very little is known about the Black Death and some researchers think that other factors, such as changing water temperatures or overfishing, might be to blame – not the untreated sewage. It is also possible that a combination of unfavourable factors have tipped the balance of the reef, causing the disease to go rampant. Temperature does appear to be a key variable associated with outbreaks, but it remains unknown if a temperature change alone is capable of causing this degree of devastation.

Molecular studies on lesions have not been able to identify a likely microbial pathogen, and according to Chen, the black layer might actually be an opportunistic second effect rather than the causative agent of the coral mortality. Montipora aequituberculae corals seem to be especially susceptible to the disease, but at least five other coral species from three different genera have been affected as well.

When Chen surveyed the water of Green Island last year, only four colonies off Dabaisha or Great White Sand showed signs of Black Death. In April this year, Chen found 24 affected colonies – six times as many as last year. If nothing is done to remedy the problem, Great White Sand near the southernmost tip of Green Island may have only dead colonies in five to six years, Chen predicts.

Green Island

Green Island is known as one of the world’s best spots for scuba diving and snorkelling. Located roughly 16 nautical miles southeast of Taitung on east Taiwan, Green Island used to house a concentration camp for political prisoners. Today, it is instead famous for its rich coral reefs.

(The picture is not from the green island but rather the great barrier reef)

Vandenberg sunk in 1 minute and 54 seconds

As reported earlier here and here, the retired 523-foot military vessel “Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenberg” was scheduled to be sunk this month to become an artificial reef off the Floridian coast, and we can now happily report that everything has gone according to plan.

After being slightly delayed last minute by a sea turtle venturing into the sinking zone, Vandenberg was successfully put to rest roughly 7 miles south-southeast of Key West at 10:24 a.m., May 27.

Once 44 carefully positioned explosive charges had been detonated, Vandenberg gracefully slipped below the water’s surface in no more than 1 minute and 54 seconds. It is now resting rightside-up on the sea bottom at a depth of roughly 140 feet (43 metres) in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

Divers and other underwater specialists are currently surveying the ship to make sure it is safe for the public to explore. Hopefully, Vandenberg will open up for public diving by Friday morning.

Over 20 cameras were mounted on the vessel to capture images of it descending into the blue, cameras that are now being retrieved by an underwater team.

Vandenberg is the second largest vessel ever intentionally sunk to become an artificial reef. In 2006, the 888-foot long USS Oriskany, also known as CV-34, was sunk in the Gulf of Mexico, south of Pensacola, Florida.

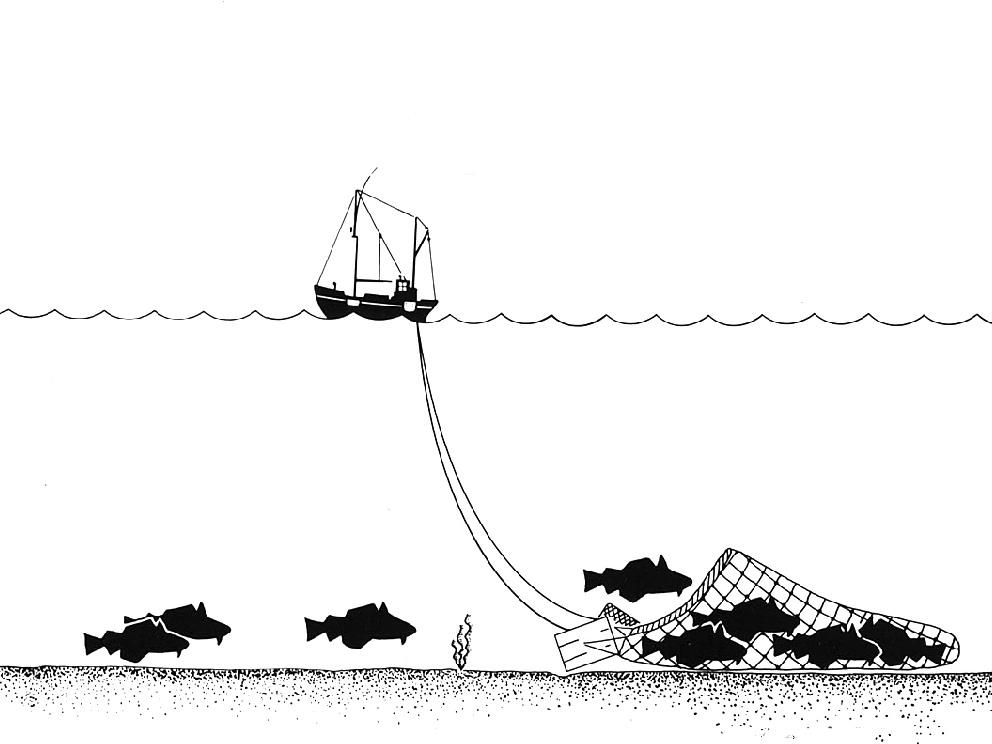

Are trawlers obliterating historic wrecks?

An example of the damage trawlers can cause is the wreck of HMS Victory, a British warship sunk in the English Channel in 1744. Trawling nets and cables have become entangled around cannon and ballast blocks, and three of the ship’s bronze cannons have been displaced. One of them, a 42-pound (19 kg) cannon weighing 4 tonnes, has been dragged 55 metres (180 feet) and flipped upside down. Two other cannon recovered by Odyssey Marine Exploration last year show fresh scratches from trawls and damage caused by friction from nets or cables.

“We know trawlers work the Victory site because one almost ran us down while we were there,” says Tom Dettweiler, senior project manager of Odyssey Marine Exploration.

“It turns out that Victory is right in the middle of the heaviest trawling area in the Western Channel,” says Greg Stemm, chief executive of the company. “We were shocked and surprised by the degree of damage we found in the Channel, he continues. “When we got into this business, like everyone else we thought that beyond 50 or 60 metres, below the reach of divers, we’d find pristine shipwrecks. We thought we’d be finding rainforest, but instead found an industrial site criss-crossed by bulldozers and trucks.”

While surveying 4,725 sq miles (12,300 sq km) of the western Channel, Odyssey Marine Exploration found 267 wrecks, of which 112 showed evidence of being damaged by bottom trawlers. That is over 40 percent.

The English Channel has been a busy area for at least three and half millennia and was thought to be littered with wrecks. In these fairly cold waters, wooden ships tend to stay intact for much longer periods of time than they would in warm tropical regions. Strangely enough, Odyssey Marine Exploration found no more than three pre-1800 wrecks when surveying the area using modern technology sensitive enough to disclose a single amphora. According to historic estimations, at least 1,500 ships have been lost in these waters so finding no more than three pre-1800 wrecks calls for further investigation.

Odyssey Marine Exploration blames bottom trawlers for the lack of wrecks. “The conclusion and fear is that the vast majority of pre-1800 sites have already been completely obliterated by the deep-sea fishing industry,” says Sean Kingsley, of Wreck Watch International, the author of the Odyssey report.

Odyssey Marine Exploration is the world’s only publicly-listed shipwreck exploration company and critics argue that these American treasure hunters are overstating the damage for their own gain.

“You have to ask why Odyssey is doing such a study,” said Robert Yorke, chairman of the Joint Nautical Archaeology Policy Committee. “They want to pressurise the UK Government to allow them to get at the wreck . . . the Victory hasn’t disappeared since 1744; it’s not going to disappear tomorrow.”

The Ministry of Defence has jurisdiction over warships’ remains and it has asked English Heritage for an assessment of the threats to the site. English Heritage has a policy of leaving shipwrecks untouched on the seabed unless a definite risk can be shown.

Reef damage from snorkelers and scuba divers not widespread in Hawaii

Reef damage more limited than suspected

A new study from Carl Meyer and Kim Holland of the Hawai’i Institute for Marine Biology encompassing four protected marine sites in Hawai’i reveals that snorkelers and scuba divers only have a low impact on coral reef habitants at these sites and that the impact is limited to comparatively small areas.

The study, funded by NOAA Fisheries and the Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Aquatic Resources, is based on secret observations of snorkelers and scuba divers at four marine life conservation districts: Honolua-Mokule’ia on Maui, Kealakekua Bay on the Big Island, Manele-Hulopo’e on Lana’I, and Pupukea on O’ahu’s North Shore.

“These are areas created with the overarching goal of maintaining an environment in pristine or near pristine condition“, says Meyer. “One of the ironies is that because it’s such a nice area, a lot of people want to come and visit it, and that sets up the potential for the original goal of marine protected areas to be undermined by overuse.“

The researchers used handheld Global Positioning System (GPS) units to map the movements of swimmers in the water and identify “hot spots” where the highest amount of contacts with reefs and other substrate took place. They found that divers and snorkelers use no more than 15 percent of the total reef habitat at each studied site and that the visitors stay within comparatively small areas associated with access points.

“Although Hawai’i marine protected areas were heavily used in comparison to those in other geographic locations, this did not translate into high recreation impact because most fragile corals were located below the maximum depth of impact of the dominant recreational activity (snorkeling),” according to the report.

The Meyer and Holland study provides information on a subject suffering form a severe shortage of reliable data.

“A lot of work on marine protected areas has focused on what the marine life is doing, not people,” saysMeyer, who hopes that information from the study will be used to create designated access points and boat moorings to focus activities away from the most sensitive parts of the reefs. By looking at a dive site’s topographical features, it is possible to predict where snorkelers and scuba divers are most likely to proceed from an access point.

“If you manage those access points somehow, you can determine where people go,” Meyer explains.

Boat access vs. shore access

According to data retrieved from the study, boat access has a lower impact per dive than shore access, for several reasons. People that dive and snorkel from a boat do not access the site from land so there is no wading involved, but information and supervision also seem to play a major role.

Divers and snorkelers on tour boats are instructed on proper reef behaviour before going into the water and they are also monitored by dive tour staff.

“If people are doing things they are not supposed to be doing, I’ve seen them intervene, and that separates boat-based activities from shore-based,” says Meyer.

Shore-based snorkelers and divers may of course receive instructions from shops where they rent their gear, but they will not be as strictly supervised during the actual dive as those who access from tour boats. There is less on-site management at dive spots accessed from shore, Mayer says.

According to the study, most of the substrate contacts between reef and humans occurred at shoreline access points where people waded to enter and exit the ocean. Even in such areas, the reef impact level was low since the contacts mainly involved sand or rocks where no coral grew. (The study does however point out that we “cannot rule out that (coral) colonization is being prevented by continued trampling.”) Only 14 percent of the contacts were between humans and live substrates, such coral, coralline algae, or invertebrates living attached to the substrate, and less than 1 percent of the contacts caused apparent damage, e.g. tissue abrasions or broken branches. Most of the damage was caused by snorkelers accessing from the shore. Scuba divers do however have a greater average impact on coral per dive than snorkelers, chiefly because scuba divers stay down longer each dive, explore a larger area, and venture deeper down.

Impact would be slashed in half if 16% of visitors stopped acting like morons

As in many other parts of the world, a major part of the damage is caused by a comparatively small part of the population.

“One of things we noticed is that about half of the physical impacts that we observed in these areas [shoreline access points] resulted from only 16 percent of the people who are using it,” Meyer says. “There is a subset of people who have a much higher impact. If you can reach that 16 percent, you could literally halve the existing impact.”

Meyer suggests placing educational signs at popular dive sites and letting volunteers provide visitors with information and advice.

Only few places are heavily impacted by tourist, but those places are of high commercial and recreational value

Although coral trampling only damages a very small part of Hawai’i’s total reef resources, the damage naturally tend to take place along beaches and at offshore sites of high recreational value.

The state of Hawai’i’ is heavily dependant on its $800 million ocean recreation industry and managing even heavily visited areas is therefore imperative for the long-term financial stability of this island state and its inhabitants.

According to Ku’ulei Rodgers, another scientist with the Hawai’i Institute for Marine Biology, increased visitor use results in a clear pattern of decreasing coral cover and lower fish populations since popular reefs can’t recover from damages while being continuously trampled.

“It can do really heavy damage to have people standing on the reef, but the good news is there are few places where there is a heavy impact from tourists. It’s mostly concentrated in places like Waikiki and Hanauma,” she said.

During the last fiscal year, the lower beach at the renowned snorkelling site Hanauma Bay was visited by 780,000 people. This can be compared to the areas studied by Meyer and Holland where the most heavily visited site, Kealakekua, was visited by roughly 103,300 snorkelers and 1,440 divers annually. Honolua-Mokule’ia received 84,000 snorkelers and 2,050 divers, Pupukea 47,700 snorkelers and 22,500 divers, and Manele-Hulopo’e a mere 28,200 snorkelers and 1,750 divers.

Closure, permit only or mandatory guides

In some situations, education and information simply isn’t enough. Last year, people straying onto unmarked coastal trails and trampling reefs at two popular snorkelling coves (the Aquarium and the Fish Bowl) forced managers of the ‘Ahihi-Kina’u Natural Reserve Area in South Maui to close much of the reserve’s 2,045 acres.

“It was a big step for us,” says Bill Evanson, Maui District natural area manager for the Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR).

The closure took place in October and will be in effect for two years to give damaged areas a chance to recover. An advisory board is currently considering whether to allow future access by permit only or through guided hikes. Before the closure, the ‘Ahihi-Kina’u Natural Reserve received 700 to 1,000 visitors a day.

The ‘Ahihi-Kina’u reserve was created for conservational reasons and is home to some of Hawai’i’s oldest reefs. Within the reserve, you can find rare anchialine ponds as well as numerous extraordinary geological and archaeological features.

Even though the reserve has only been closed since October last year, there are already noticeable signs of recovery.

“We’re seeing that many of the tide pools and coves where there used to be people are inhabited by fish in numbers and variety we haven’t seen,“ says Evanson. “Fish aren’t being scared away by the presence of people. Now they are able to feed, hide from larger predatory fish and breed.“