Tag Archives: Great britain

Salmon Seen Leaping From Waters of the River Derwent for the First Time in Two Centuries

After two centuries and 80 kilometers inland, an amazing thing has happened on one of the largest rivers in Britain – a salmon was seen leaping its way upstream to spawn.

This amazing thing – which is more common in Scotland and Canada – was seen in Derbyshire on the Rover Derwent.

The salmon – which would have swum to the ends of the earth just to spawn and perish – had an easier time making its way up the river due to the higher water levels because of recent rainfall.

Experts are keeping their fingers crossed, and by building “fish passes” around the weirs, hope to encourage a more permanent presence of the salmon.

Salmon need to be able to make their way upstream to breed, and Jim Finnegan – an Environment Agency expert – has commented that everything should be done to try and make this process easier.

He said: ‘We have been down there and seen salmon trying to leap over the weir.

‘But the ultimate objective is to see them spawning or breeding in the Derwent, and there’s no evidence of that yet.

‘We will need to build these fish passes.’

Well, the good news is that the salmon are making their way back up to Derwent. This means, that with a little bit of work and care, that we as humans can help mother nature return to its natural course.

Heat wave makes basking sharks head for northern shores

After being boosted by the recent heat wave, massive amounts of zooplankton is now attracting record numbers of basking sharks into British and Irish waters.

Last year, 26 basking sharks were reported from the most southerly headland of Cornwall during a 10 week long period. This year, 900 sightings have been recorded since the beginning of June.

“Last year we had a really poor year because of the weather. But even though temperatures have obviously picked up, we never expected to see the sharks in such large numbers,” saysTom Hardy of Cornwall Wildlife Trust, coordinator of the south-west basking shark project.

Record breaking numbers of basking sharks are being reported from the other side of Irish Sea as well. In June alone, the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group reports having seen no less than 248 basking sharks.

“In a three-day period we tagged more than 100 sharks in just one bay in north

Donegal,” says Simon Berrow of the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group. “You only ever see five or six of these creatures on the surface, which doesn’t reflect what’s going on under the water.”

From the Isle of Man, 400 sightings have been reported since early May.

‘”We saw a lot more in May than is usual and after a couple of quiet weeks sightings are picking up again,” said Fiona Gell, marine wildlife officer for the Isle of Man government.

Very little is known about the basking sharks, but the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group is currently carrying out a pioneering tagging project in hope of furthering our understanding of these basking giants. Simultaneously, the 47 wildlife trusts found across the UK, the Isle of Man and Alderney are working to identify basking shark hotspots.

Mile-long super pod consisting of over 1,500 dolphins spotted.

This Sunday, a mile-long super pod consisting of over 1,500 dolphins was encountered by eight lucky Sea Trust volunteers off the coast of Pembrokeshire, UK.

The volunteers were doing a small boat survey when suddenly confronted with what they first thought was a blizzard in the distance.

“As we approached, we realised that the ‘blizzard’ was thousands of gannets* spreads out over a mile or more,” said Sea Trust founder Cliff Benson.

The enormous pod, consisting of adult dolphins and their offspring, formed a veritable wall as they hastily rushed thought the water, probably in pursue of fish.

“They just kept on coming pod after pod passing by the boat some came and looked at us but most just kept on going”, said Benson. “The gannets were like an artillery bombardment

continually diving in with an explosion of spray, just ahead of the line of dolphins.”

According to Benson, the pod was most likely the result of many smaller pods that had joined together to follow a huge “bait ball” of fish.

In August 2005, a similar super-pod was filmed off Strumble Head, and last weeks spotting of a second one has caused Benson to suggest that super-pods might be a regular phenomenon in these waters.

* Gannets are a type of large black-and-white birds.

Koi crime wave in East Yorks, UK

Twelve thefts of exotic fish and pond equipment have been reported over a three-week period across Hull, East Yorks.

Humberside Police Community Support Officer Sam Gregory said all the evidence suggests the culprits are using the Internet to seek out their targets.

A picture of a kohaku Koi carp in a pond Copyright www.jjphoto.dk

“Google shows what is in your garden and you can see people’s ponds“, Gregory explained.

“One of the properties targeted has an eight foot fence and is set back from the road. The pond is in the corner and can’t be seen. Unless you were standing right next to the wall, you wouldn’t be able to hear the running water.”

In association with one of the thefts, where four small koi carps and some expensive lilies were taken, a neighbour report seeing two young men with a bike with a box on it and a big black net.

“Criminals could use maps, phones and getaway cars but no one would argue that these technologies are responsible for the crime itself, that responsibility lies with the perpetrator”, a Google spokesperson said, adding that Google is just one of several providers of detailed satellite images.

A record breaking 50 basking sharks tagged in Irish waters

Scientists tagging sharks off the Irish coast have tagged a surprisingly high number of Basking sharks this year: 50 specimens in just three days.

“I would normally expect to be lucky if we tagged 50 in a whole year,” said Dr Simon Berrow of the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group.

Basking SharkA record

Together with National Parks and Wildlife Service conservation ranger Emmett Johnston, Dr Berrow set out earlier this week to tag sharks off Donegal, as part of a project funded by the Heritage Council.

“In two hours last Monday we tagged 23 sharks, and we found 19 the following day – four of which had been tagged the day before,” Dr Berrow said. By the third day, they had tagged their 50th basking shark.

Basking sharks were once a significant source of income for Irish whalers and the coastal towns of Galway and Waterford did for instance have street lights lit with basking shark oil as early as the 18th century.

The importance of Basking sharks in Irish culture is evident in the number of names and monikers give to these peculiar creatures. In Irish, this “monster with sails” is known under the names Liabhán chor gréine (Great fish of the sun), Liop an dá (unwieldy beast with two finns) and Liabhán mór (great leviathan) – just to mention a few. The epithets “Fish of the sun” and “Sunfish” both pertains to its fondness of swimming just under the surface.

In the mid-1970s the Irish stopped their whaling, but the problems weren’t over for these sharks since they frequently ended up as by-catch in drift nets; a fishing method now outlawed in Irish waters. In addition to this, Norwegian whalers continued to hunt for shark off the Irish coast until 1986.

The Basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, and is a protected species in Great Britain but not in Ireland. However, the European Union has just placed a moratorium on fishing for Basking sharks in these waters.

If you spot a Basking shark in Irish waters, the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group would very much like to know any details about the sighting. You can find more information at www.baskingshark.ie.

Want to know more about Basking sharks and where they head when the Northern Seas become too cold for comfort? Check out our earlier blog post on Sharks of the Caribbean.

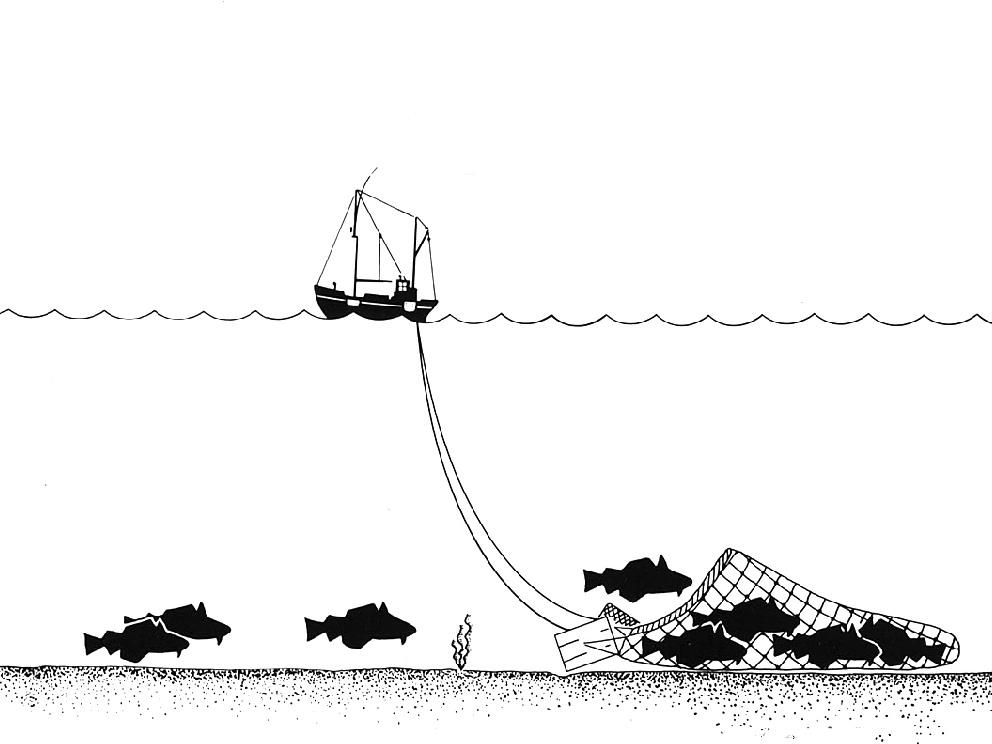

History of Trawling; not a modern problem

One of the earliest known complaints regarding trawling is in fact 400 years older than the U.S. Declaration of Independence and over two centuries older than all the Shakespeare plays; it dates back to the European Middle Ages but raises the same questions as we discuss to today: the effect of trawling on the ecosystem, the consequences of a small mesh size, and industrial fishing for animal feed.

During the reign of Edward III, a petition was presented to the British Parliament in 1376 calling for the prohibition of a “subtlety contrived instrument called the wondyrchoum”. According to the petition, the wondyrchoum was a type of beam trawl, which caused extensive damage to the environment in which it was used.

“Where in creeks and havens of the sea there used to be

plenteous fishing, to the profit of the Kingdom, certain fishermen

for several years past have subtily contrived an instrument

called ‘wondyrechaun’ […] the great and long iron of the

wondyrechaun runs so heavily and hardly over the ground when

fishing that it destroys the flowers of the land below water there,

and also the spat of oysters, mussels and other fish up on which

the great fish are accustomed to be fed and nourished. By which

instrument in many places, the fishermen take such quantity of

small fish that they do not know what to do with them; and that

they feed and fat their pigs with them, to the great damage of the

common of the realm and the destruction of the fisheries, and

they prey for a remedy.”

According to the letter, a wondyrchoum had a 6 m (18 ft) long and 3 m (10 ft) wide net

“[…] of so small a mesh, no manner of fish, however small, entering within it can pass out and is compelled to remain therein and be taken […].”

Another source* describes the wondyrchoun as ” […] three fathom long and ten mens’ feet wide, and that it had a beam ten feet long, at the end of which were two frames formed like a colerake, that a leaded rope weighted with a great many stones was fixed on the lower part of the net between the two frames, and that another rope was fixed with nails on the upper part of the beam, so that the fish entering the space between the beam and the lower net were caught. The net had maskes of the length and breadth of two men’s thumbs.”

The Crown responded to the 14th century complaint by letting “[…] Commission be made by qualified persons to inquire and certify on the truth of this allegation, and thereon let right be done in the Court of Chancery”.

Eventually, bans were introduced regulating the use of wondyrchoums in the kingdom and in 1583 two fishermen were actually executed for using metal chains on their beam trawls.

British fishermen continued to use trawl nets despite the ban, but trawling didn’t become the ravishingly successful fishing method of today until the advent of steam power and diesel engines in the 19th and 20th century.

In 1863, a Royal Commission was established in Great Britain to investigate the accusations against trawling, among other complaints. One of the arguments presented by the defence was a witness who, when asked what food fish eat, replied:

“There is when the ground is stirred up by the trawl. We think the

trawl acts in the same way as a plough on the land. It is just like

the farmers tilling their ground. The more we turn it over the

great supply of food there is, and the greater quantity of fish we

catch.”**

The Royal Commission also noted that when a trawler harvests an area already harvested by another trawler, the second trawler usually catches even more fish than the first. This was interpreted as a sign of the benevolence of trawlers, when in fact the high second yield is caused by how the destruction inflicted on the area by the first trawler results in an abundance of dead and dying organisms which, temporarily, attracts scavenging fish.

The result of the Royal Commission’s investigations was the abandonment of over 50 Acts of Parliament and a switch to virtually unrestricted sea fishing. Today, the 14th century issue of destructive fishing practises is more acute than ever.

* Davis, F (1958), An account of the fishing gear of England and Wales, 4th Edition, HMSO

** Roberts, C (2007), The Unnatural History of the Sea, Gaia

Heron ”steals” fish worth thousands of pounds

The Suffolk Police has decided to call off their investigation into the mysterious disappearance of 27 koi and seven goldfish, since the culprit turned out to be a hungry heron.

When the expensive fish disappeared from their home in Carlton Colville, UK, the police suspected human thieves and promptly issued a witness appeal which asked if locals had seen “anything suspicious” or if they had been offered similar fish. The appeal was however recalled soon, as the police found out the true identity of the perpetrator.

A further statement issued by police explained: “This incident is now being attributed to a large heron.”

“We take all incidents very seriously and we were worried that someone might have made off with fish worth thousands of pounds”, a police spokesman explains. “Thankfully, on this occasion an arrest wasn’t necessary.”

Venomous fish found in British river

A Greater Weever (Trachinus draco) has been found in a stretch of the Thames estuary in Great Britain. The species, which is native to the Eastern Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the Black Sea, is one of many signs of the improving health of the Thames estuary.

The weever was found after a two-year investigation carried out by the Environment Agency and Zoological Society of London and is the 60th new species found in the Thames since 2006. “The diversity and abundance of fish is an excellent indicator of the estuary’s health”, says Environment Agency Fishery Officer Emma Barton.

Flowing through London and several other urban areas, the Thames has a long history of being heavily polluted. In the so called ‘Great Stink’ of 1858, pollution in the river was so severe that sittings at the House of Commons at Westminister had to be abandoned.

So, should we fear this semi-new addition to the Thames estuary? No, there is no need to panic. This fish can deliver a very painful sting and should be handled with care, but the sting is rarely dangerous to humans – especially not if you seek medical attention.

The Greater Weever has venom glands attached to both of the spines on its first dorsal fin, and to the spines of the gill cover. The spines are equipped with grooves through which venom is driven up if the spines are pressed. A person that receives a sting from a Greater Weever can develop localized pain and swelling, and the result has – in a few rare cases – been fatal. Fortunately, there are several things you can do to make the situation less dangerous for a stung victim.

· If the wound bleeds, allow the wound to bleed freely (within reason of course) to expel as much venom as possible.

· Soak the affected limb in warm water because the toxin produced by the Greater Weever is sensitive to heat. There is no need use extremely hot water it and risk scalding the skin, because the toxin will deteriorate at a temperature of 40° C / 104° F.

· Seek medical attention.

The pain is normally at its most intense during the first two hours after being stung and even without treatment, the severe pain normally goes away within 24 hours. It is however possible for some pain to last for up to two weeks, and it is also possible for the spine to break off and get stuck inside the stung limb where it can continue to cause problems until it is removed.